Feminist

I have always been a feminist by instinct and became a feminist activist for women because of the personal discrimination I had faced. I wrote several books on feminism, MisEducation: Women and Canadian Universities and The Feminine Gaze: A Canadian Compedium of Non-fiction Women Authors and their Books. Although I consider myself primarily a biologist, and indeed have written an unpublished long essay on myself as a woman zoologist, this present essay will consider the part of my life devoted to myself as a woman, and to women in general.

My Story - Becoming an Activist

In the 1960s I had a Master’s degree in zoology and for three years taught part-time, one of two courses, at Waterloo College. The other two professors, both men, taught two courses each and were full-time. I asked if I could teach a second course too, and the men were delighted. “Then I would be full-time,” I observed. The men were shocked. “No, no,” they claimed. I would still be part-time and paid for only the two courses, receiving far less money than the men. I was expected to do the same work but remain unequal to the men.

I loved teaching, so I decided I would earn a PhD in order to have the best possible chance to become a professor. I earned my doctorate at the University of Waterloo in the early 1970s, at the same time looking after my three children, then all under six years of age. I obtained a full-time job as a professor teaching at the University of Guelph. After four years of teaching I had ‘good’ to ‘very good’ teaching evaluations from my students and 20 published papers (within world-renowned journals) and yet I was denied tenure. My credentials were equal to, and in some cases, better than that of my male colleagues who were awarded tenure. I was being forced out of the academic university environment because I was a woman.

This turned me into an activist feminist for all women but especially those in an academic environment. For the following years, I have spoken openly about sexual bias and published various books and papers detailing academic discrimination (see below for my publications). During this time, I was deeply depressed by having no job and tried without success to find a position at the University of Waterloo. The Dean of Science told me that he would never give a married woman tenure because she had a husband to support her. And he never did. Nor could I get advertised jobs at Wilfrid Laurier University; when I inquired why I had not been allowed even an interview, I found that there had been no interviews; the jobs had simply been given to male friends of the department members. The Ontario Human Rights Commission refused to allow me a hearing about this unfairness.

Fortunately, I was finally hired by students of the Integrated Studies (later Independent Studies) program at the University of Waterloo in 1986. Within this program, we had support groups where women discussed the discrimation they faced and we would strategize around how to fight and “move the needle” for the women who would come after us. I continued to write and work with students on women’s issues and rights over the coming decades and inspire female students. I remained with the program until it was discontinued in 2018.

Gender Exhibit: Stimulating thought and conversations

Over the years, I have written poems and short stories about my views on gender within society. I was often met with resistance for my views and observations but I persevered because I was passionate about the issues.

With this work, I have developed an exhibit of 10 poems accompanied by personal artifacts and photographs related to the topics/writings. My goal is to share this work with men and women alike to stimulate conversation and deeper reflection about the topics.

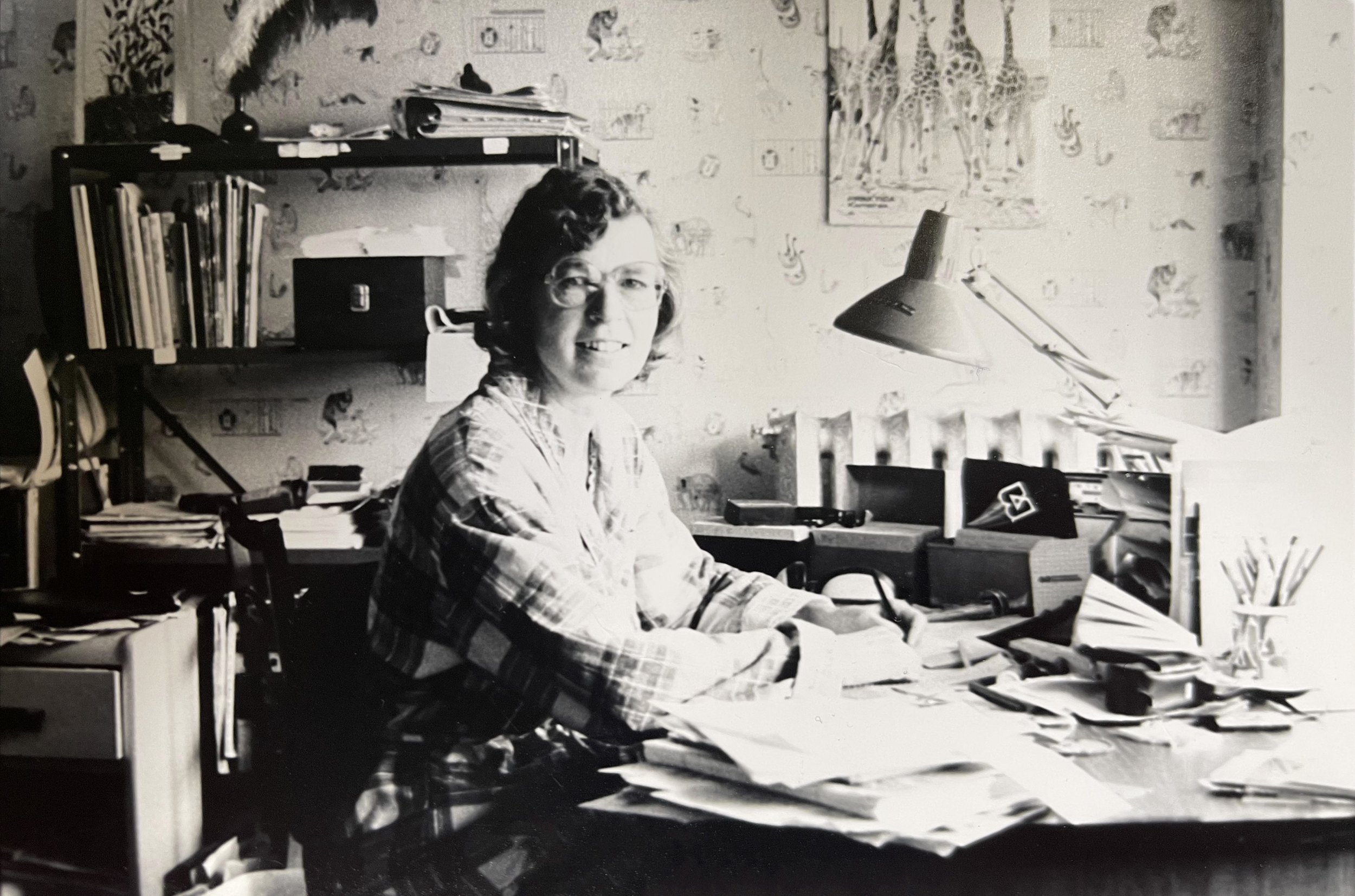

Photo courtesy of University of Waterloo (Corina McDonald).

The exhibit was first displayed at Innis College (named after my father, Harold Innis), University of Toronto. It continues to be displayed at various universities across Southern Ontario, Canada.

A full compilation of all of my poems/short stories including gender and other experiences, are available on the online store, Perspectives: Gender Roles, Stages of Life and Reflections. All proceeds of the sale of this book will be donated to the Canadian Association of Girls in Science (CAGIS) to be used towards annual membership fees for girls facing financial hardship.

Gender Related Publications: Learning more about my opinions about women and feminism

The following are the books and articles I wrote over the years about feminism and women.

Mary Quayle Innis - The Woman Who Inspired Me

From small-town Ohio to Toronto’s social elite: This intriguing biography offers an inside look at the life of a remarkable woman, Mary Quayle Innis (1899–1972), often in her own words. She was a prize-winning student at the University of Chicago, wife of famous Canadian economist Harold Adams Innis, Dean of Women of Toronto’s University College, short story and novel author, writer on Canada's early history, editor of her husband's books, and member of high-profile committees. This book, written by her daughter, acclaimed zoologist and author Anne Innis Dagg, Member of the Order of Canada, is produced by Mary Dagg and edited by Mary Innis Ansell, two granddaughters of Mary Quayle Innis.

Published by Otter Press, 2020

Human Evolution and Male Aggression - Debunking the Myth of Man and Ape (with Lee Harding)

"Should be widely read and incorporated into both high school and university curricula because the myths they challenge are so deeply embedded in mainstream society and are perpetuated and legitimated ... an eye-opening book that will definitely change many people's thoughts about men and violence." - Literary Review of Canada

Published by Cambria Press in 2012

The Feminine Gaze: A Canadian Compendium of Non-fiction Women Authors and their Books (1836-1945)

Many Canadian women fiction writers have become justifiably famous. But what about women who have written non-fiction? When Anne Innis Dagg set out on a personal quest to make such non-fiction authors better known, she expected to find just a few dozen. To her delight, she unearthed 473 writers who have produced over 674 books. These women describe not only their country and its inhabitants, but a remarkable variety of other subjects: from the story of transportation to the legacy of Canadian missionary activity around the world. While most of the writers lived in what is now Canada, other authors were British or American travellers who visited Canada throughout the years and reported on what they found here. This compendium has brief biographies of all these women, short descriptions of their books, and a comprehensive index of their books’ subject matters.

Published by WLU Press in 2001

Women’s Experience, Women’s Education – An Anthology (edited by Anne Dagg, Sheelagh Conway, Margaret Simpson)

“To grow up female in a patriarchal society is to be encouraged to perceive oneself as one who never ‘knows’, since one’s knowledge, experience and insight are not socially valorized.” Baert, 1990

In every learning facet of our society, women have come to knowledge constructed by men for the benefit of enlightening men. Within this culture, women have been attending schools and universities for over 100 years and still, the formalized educational system has not recognized the learning perspective and quest for knowledge by women for women. The acquisition and promotion of knowledge in today’s society is still based on the perceptions of men about things that interest men. We launched this anthology because women have essential knowledge to share and to be validated by the global, learning community.

Many female authors contributed to this anthology and includes an article by Anne Dagg, Manipulating Data Women in Scientific Research.

Published by Otter Press in 1991

Note: a hard copy of this book is available by contacting: mary@anneinnisdaggfoundation.org

MisEducation: Women and Canadian Universities (with Patricia Thompson)

“This book is a must for every professor, university administrator, and politician. Any woman who has had contact with a Canadian university will read her own untold story here.” Sasha McInnes

“This is not only an original testimony but a very brave and honorable text…The patriarchal forces which pervade our university systems must be held accountable for their abuse of women academics and students.” N. Kathleen Minor

Published by OISE Press/The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education in 1988

Note: a hard copy of this book is available by contacting: mary@anneinnisdaggfoundation.org

The 50% Solution - Why Should Women Pay for Men’s Culture

“Women have been largely excluded from the work of producing the forms of thought and the images and symbols in which thought is expressed and ordered. There is a circle effect. Men attend to and treat as significant only what men say. The circle of men whose writing and talk was significant to each other extends backwards in time as far as our records reach. What men were doing was relevant to men, was written by men about men for men. Men listened to what one another said.” Smith, 1978

Published by Otter Press in 1986

Note: a hard copy of this book is available by contacting: mary@anneinnisdaggfoundation.org

76 Terrific Books About Women

I have chosen the following books about women for one reason only; they are wonderful books to read. I decided to compile this list several months ago, when I found my local library discarding one of my favourite books, Full Tilt, by Dervla Murphy. Presumably because this book was published fifteen years ago, it was considered too old to be of any further interest to library patrons. Never mind that is is a classic among travel books.

It seemed to me that if people were not reading and enjoying such timeless non-fiction, it must be because they did not know about it. So I have listed here those books about women I have read with great pleasure over the past twenty years in the hope that others will want to read them too.Proceeds from the sale of this book went to the Kitchener-Waterloo Status of Women Committee

Published by Otter Press in 1980

Note: a hard copy of this book is available by contacting: mary@anneinnisdaggfoundation.org

Why do People Become Feminists? (written by Anne in 2010)

I know why I became an activist for feminism but I always wondered why (and how other) people become feminists. I have included two appendices below of historical experiences as to why women became feminists through the years. These selected entries are from a manuscript I wrote called The Big Jolt, in which I examined how and why people became activists of all kinds. The selections below are specifically about people who became activists for womens’ rights. Some people I interviewed directly, others I read about their story. Each person has an interesting and compelling story as to what “jolted” them into becoming an activist and subsequently lead them to accomplish notable/important/significant things to move feminism forward in society. Some stories are more dramatic than others but every woman was passionate, courageous and persistent in their quest/journey/path and many ultimately changed history.

Appendix A

Becoming a Feminist – By Personal Experiences

Sonia Johnson was a committed member of the Mormons when she and some friends began looking into the Equal Rights Amendment of the United States which was opposed by her church (Johnson, 1989, 103ff). She was relieved when her church group was told that their state president (an important church official) was coming to explain the church's position on women's rights.

Johnson's group contained three women with doctorates and three with master's degrees, so the women were nonplussed when the official stated that his remarks were based on an article he had just perused in Pageant magazine. She writes, "A fury like none I'd ever felt before anywhere for anyone began to boil up inside me." She knew that if men’s human rights were being considered, the president's presentation would have been thoroughly prepared. Women's rights, by contrast, were trivial so that he did not feel any need to inform himself about them before going forth to teach and work against them.

The president went on to read the official church letter which stated that Mormon women were loved and exalted by their church. Johnson was so incensed by this patronizing statement that she suddenly realized that for all her life she had been duped about patriarchy. She went on to work for the Equal Rights Amendment which resulted in her expulsion from the church, up until that time the focus of her life. She gave public speeches, organized conferences, and wrote books about the women’s movement.

Margaret Gillett (b 1930) was a scholar rather than an athlete who grew up in Australia (Gillett, 1984, 409-10). She became a teacher in New South Wales after receiving her post-graduate Diploma in Education. Her first job was in Bourke, in the arid outback. She writes, "The futility of trying to teach the required Merchant of Venice in that environment was overwhelming. But what was really aggravating about this, my first real job, was that I was paid only three-quarters of what my male counterparts received. The government salary scales announced the male/female discrepancy blatantly.” Both men and women worked hard to teach their pupils. How could it be assumed that the men would do a better job and therefore should be paid more?

In the face of such open discrimination, Gillett felt she had to act. She states, "I joined the Teachers' Federation and went as a delegate to a conference in Sydney where the issue was equal pay, and where we marched down Macquarrie street to the State Parliament to press our case." Despite the obvious unfairness of the wage scale, Gillett found that many of her colleagues approved of neither the means nor the ends of this protest. Even so, she knew she was right. In time she became a professor whose research has focused on women and on education. Her books include two about women who worked at and who attended McGill University where she taught. And the double wage scale for men and women was made invalid in Australia by the 1970s.

Another scholar, this time a scientist, was Alma Norovsky (a pseudonym) who had a checkered life becoming a theoretical physicist (Gornick, 1983, 90,92-3). Although she worked hard to earn her PhD and did good research, she was never accepted as an equal by male physicists. She married and had children but with little support from her husband, this held her back too. However, her problems always seemed to her like personal problems.

Then she talked to a woman in high energy physics. "We compared notes. It was astonishing how similar the pattern of our lives had been! For the first time it hit me that my life had developed as it had because I was a woman, and I'd made women's choices, and ended up where women in science end up. It hit me like a ton of bricks. All at once, I saw everything. From that moment on I became a rabid feminist. And I mean rabid."

Shortly after that her marriage fell apart, but she also landed a university position. Norovsky says of her colleagues at the university, "They're very theoretical. People are always asking me how women are treated here. Women? I answer, they're a theoretical concept."

Some women became feminist activists after attending women's meetings that inspired them: a hearing, a women's caucus, consciousness raising sessions, an International Women's Day celebration. Several jolts have activated Gloria Steinem at different periods of her life, but one of the biggest was attending events concerned with the abortion law (Pearson, 1994, 58ff). Steinem had been assigned to cover an abortion hearing for New York magazine in 1969. She says, "The state was trying to decide about the abortion law and the review committee was slated to hear testimony from 19 men and one nun. Some women had organized a counter hearing in an East Village basement, and I'd never seen anything like it in my whole life. I'd had an abortion but I hadn't told a soul. None of us spoke about things like that. And here was this room full of women telling their stories."

These revelations, and the fact that the official hearing was taking place without the input of any women who might have had an abortion, gave Steinem's life a whole new direction. As a founder of Ms magazine and a feminist activist and writer, she has never looked back.

Rita MacNeil, who would attend a Women's Caucus, grew up in poverty, one of eight children with an unhappy mother who did not want her daughters to marry and live as she did (Kostash, 1975, 126-8). When she was 19 and hoping to make a career in music, MacNeil became pregnant instead by a man who then left her. After the baby was born, she married another man and set up housekeeping in suburban Toronto. She soon felt depressed and trapped there, but she didn't know why.

MacNeil's life changed dramatically in 1971 when she attended the Women's Caucus in Toronto with a friend. She had always felt supported by women, by her sister, her friends at school, her co-workers at Eaton's, so she was willing to take women seriously. She told an interviewer, "Oh my goodness, I'll never forget when I walked in there, I was so scared. I didn't go out much or do many things, and this whole roomful of angry women is something I'd never been in before. Oh God, I'll never forget. It was so exciting. I came out of there all fired up. That sounds so stupid. Oh dear, it's like, before that I was one thing and after it something else." The group had talked about the need of access to abortion, an issue that was very real to her.

After this meeting, she went home and wrote a song. She didn't feel able to make speeches about women's issues, so decided that instead she would sing about them. As Myrna Kostash remembers, "In due course, Rita MacNeil became an integral part of the Toronto women's liberation movement. Where feminists gathered, to protest, demonstrate, celebrate, there was Rita, in the sun, the wind, and the rain with banners flapping around her, singing against the hostility and jeers of passers-by, whipping up the energy and solidarity of the women, spreading out over those who would listen the glory of her voice joined with the momentum of her courage in letting it all out, telling her story, describing the rage and the pain, reviewing the growth of sisterhood and feminist politics, so that no woman who heard her could stay unmoved. Along with her own voice she had found one for all of us." MacNeil not only became an ardent feminist, but as a successful singer she would have her own show on national Canadian television.

Yvonne Johnson went to her first International Women's Day celebration because of her lover, not because she believed in feminism (Hughes, Johnson and Perreault, 1984, 174). She admired the style of one of the speakers, a woman of her own age who waved her arms around and cared passionately about politics and ideas-- she was making connections between loving other women and feminist analysis. Johnson assumed she must be an academic woman from a privileged background. But the speaker then began talking about her own life-- how poor she had been as she grew up, how she had been involved with men before she fell in love with a woman. Johnson realized that they had similar histories and liked her sense of humour. She says, "I was so surprised to discover a perfectly ordinary woman (like me) who had managed to find something powerful and sustaining and reassuring in these ideas called feminism. I actually walked into the room, sat down, and eventually asked about the group she belonged to. I mean what was there to lose? Women like that obviously had found something that made them happier and stronger-- and if it could make sense to a woman who was like me, then it surely could be good for me." Johnson subsequently became involved with feminist activism and co-authored the 1984 book, Stepping out of Line.

Birgit Voss (b1948) came from a group of women talking about themselves (Voss, 1988, 174). She left Germany in 1967 to come to England, married young, and soon had a daughter. She was always interested in religion and spirituality, questioning why things were the way they were.

For Voss, consciousness-raising sessions were pivotal in changing her perspective on life. "I remember well the blinding fury, the brilliant anger, the sense of betrayal I felt and shared with many of my sisters when, through consciousness-raising, we unraveled the patriarchal plot; I remember the joy when we allowed ourselves to feel love for women instead of the negative feelings normal in a misogynistic society. Before we can find love, before we can share it and love others we have to find the love we have for ourselves. I believe that without a feminist perspective it is very difficult indeed for women to create this love for themselves."

Two women became feminists because of two comments, one thrown out casually by a professor and one made by a sympathetic dentist. The first example is quickly told (Driscoll and Thomson, 1991).

Marilou McPhedran was jolted out of her complacency when, as a student at Osgoode Hall Law School in Toronto, she overheard a comment from her criminal law professor, "Don't they know that girls are for f***ing?" The enormity of these few words hit her like a sledgehammer. Did this professor, and probably other professors too, care nothing about all the work women had done to be admitted to law school? Did they think that only a man could be a good lawyer? Was the cause of justice only a sham? McPhedran became not only a lawyer, but an ardent feminism who has worked hard for women in her profession.

Barbara Noël received her big jolt from a pro-feminist dentist (Noël, 1992). Indeed, it was because he was a man, rather than a woman, that she really listened to what he was saying. Noël had been sexually and medically abused by a world-renowned psychiatrist for 18 years. While still undergoing therapy in l982, she met a dentist, Dr. Robert Wheeler, who was able to cure a chronic displacement of her jaw which had caused her years of pain. None of the many doctors she had visited earlier had recognized her problem.

He said to her, "We live in a male chauvinistic society, where people in the marketplace and men who are doctors tend to think women are crazy anyway. When a woman comes in and says, “I have these terrible headaches, and my neck hurts”, the doctor can't see any visible anatomical reason, he assumes she's stressed or crazy and says, “Maybe we should medicate you with some Valium or you should see a therapist."

Until that moment, Noël had never heard a man say anything about sexism. She wrote, "When Betty Friedan or other women said this sort of thing, I always thought they sounded so angry that it didn't get through to me. Hearing a man-- and a doctor-- say it shook me up and jarred me into realizing the truth of what he was saying. I didn't realize at the time that the way I dismissed women and believed men was a dramatic sign of my own unexamined sexism, and showed how I had accepted the status quo without question." From that moment on, she was able to see the world through new eyes. Exactly the same message about sexual discrimination was disregarded by Barbara Noël when it came from women, but appreciated and accepted when it came from a man.

Andrea Dworkin became an ardent feminist because of her experience within the civil rights movement in the Deep South in the 1960s (Barlow, 1998, 19). Because a Black activist was missing, his colleagues dragged a local swamp to see if he had been murdered and his body thrown there. They found lots of bodies but they were all women, black and white. These corpses didn’t worry the searchers–- they probably belonged to hookers they thought, and need not be reported. “These men who so readily dismissed what they had found were not local rednecks; they were her compatriots in the civil rights struggle.” Dworkin was so horrified that she became a raging prophet in the fight against the abuse of women for many years. Her book, Women Hating is an anthology of state and religious oppression of women through the ages which itself raised the consciousness of many other women.

Bibliography

* Aisenberg, Nadya and Mona Harrington. 1988. Women of Academe. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

* Barlow, Maude. 1998. The Fight of my Life.

* Dagg, Anne Innis and Patricia J. Thompson. 1988. MisEducation: Women and Canadian Universities. Toronto: OISE Press.

* Driscoll, Katie and Dave Thomson. 1991, Mar 29. McPhedran brings tales of professional sexism. University of Waterloo Imprint.

* Gillett, Margaret. 1984. "Next time,... Bargain Harder". In Margaret Gillett and Kay Sibbald, eds. A Fair Shake, pp 407-421. Montreal: Eden Press.

* Gornick, Vivian. 1983. Women in Science. New York: Simon and Schuster, pp 90, 92-93.

* Harris, Pamela. 1992. Faces of Feminism. Toronto: Second Story. * Hughes, Nym, Yvonne Johnson and Yvette Perreault. 1984. Stepping out of Line. Vancouver: Press Gang.

* Johnson, Sonia. 1989. From Housewife to Heretic. Albuquerque, NM: Wildfire Books.

* Kostash, Myrna. 1975. Rita MacNeil: Singing it like it is. In Myrna Kostash, Melinda McCracken, Valerie Miner, Erna Paris and Heather Robertson, eds. Her Own Woman, 109-133. Toronto: Macmillan.

* Minor, Kathleen Mary 1994. Elizabeth: An elder Inuk remembers her life. Canadian Woman Studies 14,4: 55-57.

* Noël, Barbara, with Kathryn Watterson. 1992. You Must Be Dreaming. New York: Poseidon Press.

* Pearson, Patricia. 1994, Mar. Gloria Steinem turns 60! Chatelaine, 58-61, 88-94.

* Voss, Birgit. 1988. The spiritual is the political. In Amanda Sebestyen, ed. '68, '78, '88, pp 169-174. Bridport, Dorset: Prism Press.

Appendix B

Becoming a Feminist – by Observing Others

Johnnetta Cole was the first Black woman president of Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia (Bateson, 1989, 45-46). She grew up in Jacksonville when Florida was much deeper in its Jim-Crow tradition than it is today. Racism was embedded in all parts of her life.

Cole became aware of sexism only when she visited Cuba with a delegation of Afro-Americans in the 1960s. Their aim was to discover possible racism in the country which had recently broken away from American influence. Her group, which traveled about asking how many Blacks were hired in institutions such as hospitals and universities, was suspicious when no one wanted to answer their questions. Eventually they realized that the Cubans did not organize their society in terms of colour, but in patriarchal and macho terms. Up until that time she had been unable to conceive of a society not stratified by race.

It was a revelation to Cole to find that racism was not forever. But it made her sensitive to sexism which she had never noticed before, coming as she did from a background where all the women she knew were strong and worked outside, as well as inside, the home. She remembered racism in church-- all the faces in the stained-glass windows were white, and she sang a hymn asking Jesus to wash her whiter than snow-- but she hadn't thought consciously that men held the places in the church hierarchy while women did not.

Once Cole became aware of sexism, she began to combat it as well as racism in her life and in society. But she believes that sexism will take longer to eliminate because it is so insidious.

Anne-Marie Pharand became an out-of-the-closet feminist not only because of the massacre of women at the Université de Montréal, shot by a man who did not think women belonged in engineering departments, but because of male and media reaction to the murders (Pharand, 1990). On December 6, l989, a young man entered a classroom of the Ecole Polytechnique, ordered the men to one side of the room and the women to the other, and started shooting the women. His rampage continued until 14 women were dead, and ten women and three men wounded.

Pharand's grief at watching and hearing the news of this disaster was intense. She writes, "Little by little, my grief was replaced by a feeling of anger when I realized that the francophone media, and the journalists, whether from the TV, the radio, or the newspapers, the social workers, the male psychiatrists, the criminologists, were all denying the obvious. Almost all of them were arrogant in their attitude and words. They talked about the victims; they were hesitant to clearly state they were women. Several of them would not even link this massacre with violence against women."

Later, at the funeral, she noticed that men took over the ceremony and advocated in their speeches that men and women be equal in society, "This in the Church which itself refuses to apply this principle by rejecting women from the priesthood and by denying them any real power in its structures. It is insulting and offensive!"

Anne-Marie Pharand joined the women's movement and, as she says, “I will be part of it until the day I die."

Other women became feminist activists after watching friends or relatives play out sexist roles, as if they were watching a film of the lives of these people. The content of these films changed the way they thought about men and women forever. For example, a Saudi Arabian princess (who remains anonymous for her own protection) became radicalized as a young girl when she observed the power of men to harm women, even those related to them (Sasson, 1992, 28,44). Her jolt came when she saw what happened to her older sister, Sara. Sara was not only beautiful, but highly intelligent. She wanted to study art in Italy and be the first to open an art gallery in Jeddah. In her early teens she poured over art books of the great masters, making lists of the places she planned to visit in Florence, Venice and Milan. Her father, however, wanted a close tie with a leading merchant family so he arranged when she was 16 for her to be the third wife of a 62 year old man she had never met. She was drugged with tranquilizers so she wouldn't make a scene on her wedding day. Her new husband treated her with such sexual brutality that she tried to kill herself five weeks later. Her father then reluctantly agreed that she might divorce her husband.

Noting the horror of her sister's life, the princess resolved that women must have a voice in deciding whom they would marry, a decision that altered their lives forever. "From this time, I began to live, breathe, and plot for the rights of women in my country so that we could live with the dignity and personal fulfillment that are the birthright of men."

Following up her resolve, the princess formed a small group called Lively Lips made up of her stepmother, Randa, who was a year older than she, and two friends from wealthy families. The group's aim was to battle the silent acceptance of women's submissive role in society, in part by trying to prevent marriages of young women to old men. However, in a bid for freedom, the two wealthy young women were driven to desperate acts.

They often had a driver leave them in the market, from where, fully veiled, they would go to a nearby apartment to pick up young men. Sometimes they went to a man's room and played sexual games, although never removing their veils or allowing sexual intercourse. Eventually they were arrested for their behavior and turned over to their families. One was married as a third wife to an old man who lived in a distant village, and the other was drowned in the family swimming pool while her relatives watched. The princess' father divorced Randa, his fourth wife, while the princess herself was chastised. However, she did not give up her work for women's rights. She later carried on the aims of Lively Lips by supplying the material to Jean Sasson for the best-selling book, Princess.

Another example was Gloria Steinem who by the late 1960s had picketed for civil rights, against the United States involvement in Vietnam, and with migrant farm workers, but never for people like herself, white middle class women (Steinem, 1992, 24-25). She writes, "When Blacks or Jews had been kept out of restaurants and bars, expensive or not, I felt fine about protesting; so why couldn't I take my own half of the human race (which, after all, included half of all blacks and half of all Jews) just as seriously? The truth was that I had internalized society's unserious estimate of all that was female-- including myself. This was low self-esteem, not logic."

When Steinem was asked to go to lunch with a group of distinguished women at the Plaza's Oak Room, a public restaurant which only served men, she declined. The group expected to be refused entry, and then to picket and be interviewed by the media, which is what happened. Steinem argued that feminists should work first for more disadvantaged women who would never dream of eating in such an expensive place. She didn't want the image of feminists to become synonymous with middle class women. However, she writes, "All the excuses of my conscious mind couldn't keep my unconscious self from catching the contagious spirit of those women who picketed the Oak Room. When I faced the hotel manager again, I had glimpsed the world as if women mattered. By seeing through their eyes, I had begun to see through my own." She went on to become perhaps the most high-profile feminist activist in the United States.

Australian Lynne Spender replayed in her mind the experiences of groups of women rather than individuals (Spender, 1984, 126-7). She became committed to feminism when she visualized women's experiences as a whole, rather than individual stories. This happened in Canada at a social event, where she noticed that the two sexes became segregated into two groups, just as happened in Australia; it wasn't just an anomalous trait of Australian men to be contemptuous of women, she thought, but of men of other nationalities, too. She realized, "The men's conversation-- which for years I had felt eager to join on the premise that it was more intellectual and stimulating than that of women-- centered around boys' games-- politics, sport and dirty jokes-- while the women's conversation, from which I had divorced myself, focused on the social arrangements necessary for nothing less than the survival of the species. I have not been seduced into considering men's values and men's discussions more prestigious than those of women."

In Canada she tested her new-found self-esteem. While she was working in a garden, a male authority told her she should pull out a particular plant with a colourful blossom because it was a weed. They argued about what constituted a weed. She was elated that she felt strong enough to keep the weed because she liked it, despite the man's insistence it should be destroyed.

She writes, "From that time, 'who said?' has become a basic tenet of my philosophy as I re-evaluate the rules which have been presented to me in a male-dominated society. It is now part of my fabric that I do not have to accept that because men have said so, and because they have been saying so for centuries, their word is law." Lynne and her sister Dale are two of Australia’s most ardent feminists.

Some women became feminists not because of a short string of events in the lives of people they knew, but because of sudden images, either actual or pictured, that suddenly opened the door in their minds to a whole new concept of the social universe.

Sheelagh Conway was brought up in rural Ireland as a strict Roman Catholic (Conway, 1987, 155,245). Catholicism was a way of life for her and her family; she loved as a girl to watch the priest at mass, the swish of his long robes, the resonance of the Latin. As she grew older, she began to notice the discrepancy between the portrayal of the church as the champion of the poor and disabled and its callous treatment of women. And it was the feminist analysis of this discrepancy that enabled her to understand how the Catholic church perpetuates the oppression of women.

Conway's unease came to a head when Pope John Paul II visited Toronto in 1984 to address the Catholic clergy of Ontario. The service was televised. Conway writes, "Amid great pomp and ceremony, he [the Pope] walked down the red-carpeted aisle of the 136-year old cathedral like a monarch. He walked slowly, regally; he smiled and waved, and his white robes flowed around him. Then in a wide-angle shot of the cathedral, viewers saw an extraordinary sight for the 1980s. The cathedral was full of men, a sea of men. There wasn't one woman present. The male priests stretched out their hands to touch the pope’s garments. This was their father. At that moment, I felt something give way within me. The death knell had been tolling for a long time now and the moment of realization had finally come. This was the end of the road for me as a Catholic woman. I was no longer willing to stay within a church that compromised my integrity and dignity as a woman."

Conway has remained a non-Catholic and an ardent feminist, fighting sexism at universities she has attended and writing a book about Irish women who have immigrated to Canada, The Far Away Hills are Green (1994).

Madeleine Parent (b1918), union organizer, was politicized as a young girl by what she saw going on in the Roman Catholic church (Paris, 1975). She was given a traditional church education, with dogma and religious instruction an integral part of her life. As a biographer puts it, "The trauma of the nuns was probably the most important experience of her entire life and the soil from which the particular shape of her future sprang. The memory of helplessness and powerlessness [at the convent school] has clung to her always, to be summoned forth, smelled, and tasted at will with the intensity of original terror."

It was not her own treatment that offended Parent at the time, but that of other girls. When she was about eight, she saw another little student at the school being chastised by the nuns because her bills weren't paid. This seemed wrong to Parent, but she wasn't sure why. She became the girl's only friend.

Later, when she was sent to a boarding convent school, she saw the horrible treatment given to the maids who were mostly from poor farming areas. She said in an interview, "They were second class on the lowest level. The nuns kept about 80 per cent of their wages to mail to their parents, and gave them one or two dollars a month as spending money when they were allowed out."

These observations showed Parent that the social practices of Roman Catholicism were very different from what the church preached. From that time on she became increasingly critical of the church and increasingly involved in social action, especially feminism. Organizing unions eventually became her full-time job.

Many women become feminists not because of something that happens to them or to other women, but because of books or articles they have read. Vina Mazumdar, for example, was a research social scientist in India. In the early 1970s she was asked to take over a government research project on the status since Independence of village women in India (Bumiller, 1990, 126-7). Mazumdar was not especially interested in women's issues, but she agreed to do so, despite warning from colleagues that it would divert her from her other larger academic concerns. As she began to go over the data already collected which portrayed the desperate condition of these women, she said in reminiscence, "The first thing I felt was shock. The second thing I felt was tremendous anger-- 'Something has to be done’. Then I began to question why even a social scientist can remain so damn ignorant."

Her report, Towards Equality, showed, "Social change, development and other trends under the heading of 'progress' had in many cases made the lives of women worse." There were far fewer jobs for them than there had been, their literacy rate was half that of men, and the custom of dowry which impoverished many families was increasing.

Her research changed Mazumdar's life. "My earlier work was only earning a living," she told an interviewer. Now her life was devoted to improving the status of rural women. She became one of the matriarchs of the women's movement in India. She established a Centre for Women's Development Studies in New Delhi which affects government policy and helps organize and train village women. In return, she has learned from those in the village that women have a unique relationship with nature, that for a woman being equal to men does not mean being unfeminine, and that there is no shame in being different.

Research also jolted Lorna Marsden (b1942), past president of several Ontario universities. She started graduate work at Princeton in sociology rather than genetics because she realized, (this was in the late 1960s), that women had little hope of a career in science (Ries, 1992). She still believed, though, that if something discriminatory happened to her, it was her fault because she was somehow inadequate. She assumed that once she had a PhD, she would be hired as a professor and move up the ladder of success in the same way men did.

Marsden came to feminism when a male professor forced her, against her will, to write a paper on what actually happens to women with PhDs. When she read all that had been written on the subject, she no longer had any misconceptions. She says, "It was a very crushing term, because it became apparent that a) you don't get jobs, and b) when you get them, you don't get promoted and even if you do, you don't get paid equally and you don't have the same access to publication and nobody takes your ideas seriously and, in fact, you're not equal at all. It was at that moment that you can label me a feminist." She has continued to work on behalf of women.

For Betty Friedan (1921-2006), research into women's lives was a practical rather than a theoretical exercise. Although she is credited with being the mother of the second wave of feminism triggered by her 1963 book, The Feminine Mystique, Friedan was not a born feminist. Rather, she was moved to write her book because of experience she gathered from other women that tallied with her own (Friedan, 1985, 9,17). She married after World War II, when she had graduated from Smith College and become a journalist. She was disconcerted when she lost her job in l949 because she was pregnant for the second time, but not unduly upset because she rationalized that maternity leave was annoying for an employer. She writes, "If you were a radical in 1949, you were concerned about the Negroes, and the working class, and World War III, and the Un-American Activities Committee and McCarthy and loyalty oaths, and Communist splits and schisms, Russia, China and the UN, but you certainly didn't think about being a woman, politically."

Friedan was forced to consider the status of women when she spent a whole year, 1956-57, asking Smith College fellow graduates from 15 years earlier about their experiences and feelings. Their answers were unnerving, and the reaction to the article she wrote about her survey eye-opening. McCall turned down the article because the male editor didn't believe it, Ladies' Home Journal rewrote it to deny the evidence so she withdrew it, and Redbook noted in a shocked rejection slip: "Only the most neurotic housewife could possibly identify." Their reactions propelled Friedan to the five-year task of writing, The Feminine Mystique and being converted to feminism in the process. She remained in the forefront of the women's movement in the United States.

Hanny Lightfoot-Klein had the unusual experience of being jolted by an article she read not only at the time, but 45 years later (Lightfoot-Klein, 1992, 54). When she reached puberty, she asked her parents a few tentative questions about sex. They replied so evasively and morally that she turned elsewhere for answers, including a popularized journal about medical matters sent to her father who was a doctor. One issue had an article by the anthropologist Ashley Montagu which dealt with the history in various parts of the world of male circumcision. She writes, "The detailed anatomical descriptions and depictions of the loathsome horrors imposed on the penises of struggling aboriginal youths filled me with nausea...."

When she was well past middle age, Lightfoot-Klein found out about female circumcision in Africa. She immediately recalled the article she had read 45 years before. She notes, "A somewhat strange and terrifying event that had happened when I was 14 years old had lain deeply repressed in the recesses of my subconscious mind. It leaped into instant awareness when I was first told about Sudanese female circumcision."

Lightfoot-Klein was so jolted by the reality and by her memory that she decided to work against female circumcision full-time from then on, making three year-long treks through Sudan, Kenya and Egypt to interview 400 women and men on this subject. She realized that female circumcision was not necessarily being stamped out, because it had come to one area in Africa 30 years before and since then had become fully entrenched; if it were not done, a woman could not marry (p 181). She wrote up her research in many scientific papers and in a book, Prisoners of Ritual.

Student Juliet Sherwood was jolted not by doing research, but by reading a book (Reid, 1989, 120). She was electrified by Virginia Woolf's confrontation with patriarchal authority in A Room of One's Own. Woolf had been sitting on the bank of a river at one of England's oldest universities, lost in thought. Suddenly she had an idea which made her spring up in excitement and stride across a nearby grassy lawn. As she writes, "Instantly a man's figure rose to intercept me.... His face expressed horror and indignation. Instinct rather than reason came to my help; he was a Beadle; I was a woman. This was the turf; there was the path. Only the Fellows and Scholars are allowed here; the gravel is the place for me" (Woolf, 1929, 9). Woolf regained the path, but the incident had chased the idea from her mind.

Sherwood said, "The words elevated from the page. I understood. A Room of One's Own hit me in a way that a book has never affected me in my life before. I was so angry .... I became acutely aware of the injustice of being a woman. It was so simple that I wondered why I had never reflected upon it before." Her eyes had been opened so that she could see life from then on from a feminist perspective.

Lynne Fernie's life was also jolted, and altered for good when she read a book, in this case one by Germaine Greer (Harris, 1992, 68). She recalls, "I remember the distinct moment when I realized that I'd been had. It was four a.m. on a Sunday morning in 1976, and I'd stayed up all night reading, The Female Eunuch. That was the night I realized that I'd been taught to interpret my life through systematically instituted prejudices which are invisibly embedded in our culture."

Since then, Fernie's perspective on life has been a feminist one which has also helped her acknowledge race and class oppression.

Mary McCarthy (1912-1989) received her Big Jolt when she read Dos Passos' The 42nd Parallel about life in the United States. She writes (1985, 201),"I can cite a case–- my own–- of a young person's being altered politically by a novel, but I cannot explain the process, let alone explain it in terms of the author's intention or literary strategies. I believe there is often something accidental in these things, as with love, which gives them a feeling of fatality."

Before she read this book, she had read others. "No doubt the fervor of emotion--an incommunicable bookish delight–- had been preparing in me for some time through other 'social' books, just as two mild bee-stings may prepare you for a third that is fatal." She had read books by Tolstoy, and Shaw's The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism and Capitalism, but they had rolled off her like water off a duck's back. But then came Dos Passos's book about the United States that changed her life, as will be described in due course.

Elspeth Wallace Baugh's life was changed forever by reading a magazine. Baugh went back to university after her six children were in school and eventually earned her PhD from Toronto’s York University in clinical psychology (Baugh, 1987). During this time, she gradually evolved from a traditional homemaker to a woman who sensed the negative consequences of this role. One lunchtime she chanced to read the first edition of Ms magazine. She recalls, "I became so engrossed that I almost missed my afternoon class. There in print before my eyes was validation of so many ideas I had hardly dared voice to myself, let alone to anyone else. In fact, women of my generation usually shared their anger and distress in a form of black humor that had the underlying theme that we were coping, and did not expect change in the way our world was structured. We did not talk to each other honestly. I cannot say I became a feminist overnight but I travelled a thousand miles that day in my mind, and for the first time began to reflect on the role of women in society and to feel real kinship with other women."

What is important in this section, though, is that many women came up to her while she was signing books in a bookstore, or after one of her talks, to tell her the most profound of all things a writer can hope to hear, ”Your book has changed my life!" They also had been sexually abused as children, but before reading her book they had been too afraid to come out and tell this truth to anyone; until they did so, they could not begin the healing process that would restore them to themselves. One woman read the book, phoned family members to tell them to read it too, and then felt her own burden lighten as they rallied to help her. "Where there had been silence for many years, her sisters and her mother were now talking honestly, supporting one another, and the future looked much brighter."

Bibliography

* Bateson, Mary Catherine. 1989. Composing a Life. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press.

* Baugh, Elspeth Wallace. 1987. A slow awakening. In Joy Parr, ed. Still Running, pp 97-107. Kingston: Queen's University Alumnae Association.

* Bumiller, Elisabeth. 1990. May You be the Mother of a Hundred Sons. New York: Random House.

* Conway, Sheelagh. 1987. A Woman and Catholicism. Toronto: PaperJacks.

* Friedan, Betty. 1985. "It Changed My Life". New York: Norton.

* Harris, Pamela. 1992. Faces of Feminism. Toronto: Second Story.

* Jay, Karla. 1988. The Amazon and the Page. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

* Lightfoot-Klein, Hanny. 1992. A Woman's Odyssey into Africa. New York: Haworth Press.

* McCarthy, Mary. 1985. Occasional Prose. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

* Paris, Erna. l975. The education of Madeleine Parent, in Myrna Kostash, Melinda McCracken, Valerie Miner, Erna Paris and Heather Robertson, eds. Her Own Woman, 89-108. Toronto: Macmillan, p 94-95.

* Pharand, Anne-Marie. 1990, June. Feelings after a tragedy: personal or collective impressions? Women's Education 8,1: 3.

* Reid, Su. 1989. Learning to `read as a woman'. Ann Thompson, ed. Teaching Women, pp 113-122. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

* Ries, Barry. 1992, Oct 22. Marsden quick to become a WLU booster. The Record, Kitchener, ON p B1.

* Sasson, Jean P. 1992. Princess. New York: Avon.

* Spender, Lynne. 1984. Lynne Spender. Robyn Rowland, ed. Women Who Do and Women Who Don't Join the Women's Movement, pp 122-129. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

* Steinem, Gloria. 1992. Revolution from Within. Boston: Little, Brown.

* Woolf, Virginia. 1929. A Room of One's Own. London: Hogarth.

* Youmans, Letitia. 1893. Campaign Echoes. Toronto: William Briggs, p 66.