A Personal History of Anne Innis Dagg as a Zoologist

Written by Anne Innis Dagg in 2000

All I ever wanted to be when I was growing up was a person who studied giraffe. I saw my first giraffe at the Brookfield Zoo in Chicago where I was visiting with my mother from Toronto when I was a toddler. Something frightened the few animals as I gazed at them so that they cantered across their cage. I was entranced. I immediately began collecting pictures of them and drawing them. For my birthdays I received small toy giraffes.

Anne Innis has loved giraffes since she was a toddler.

Anne’s stuffed giraffes, made by her mother, Mary Quayle Innis.

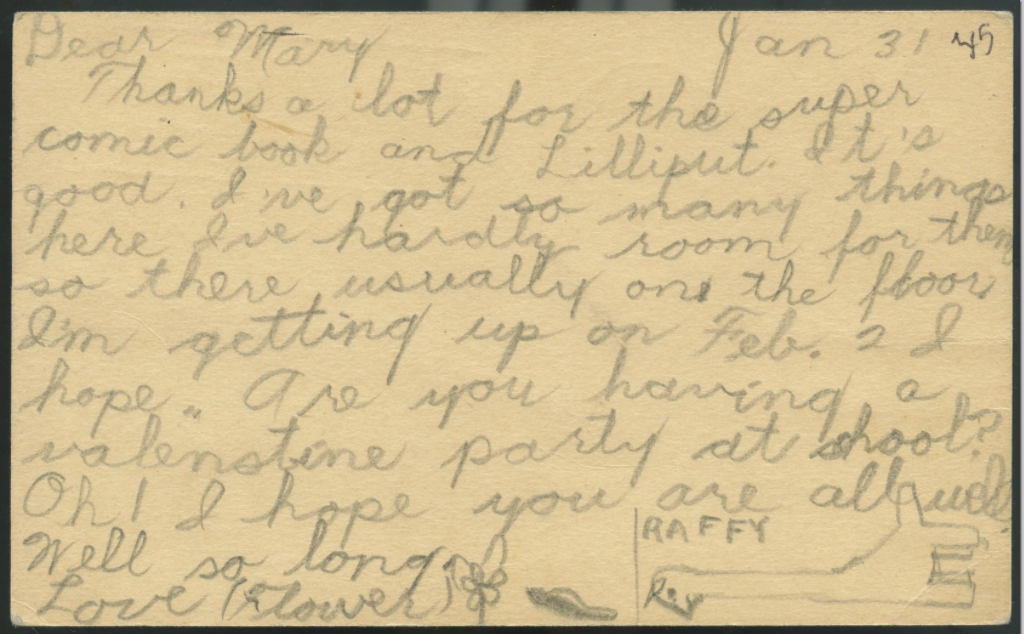

When I was 12 and incarcerated in the Riverdale Isolation Hospital for a month with scarlet fever, before the use of antibiotics, my mother sent me a stuffed giraffe she had made with a pink ribbon around its neck. I was aghast when the nurse said she would have to destroy it when I went home because it would be infectious. I wrote my mother this on one of the blank postcards (no letters) we were allowed to write and she selflessly made two more, an adult with a blue ribbon and a young one.

Postcard to Anne’s best friend, Mary W, while Anne was in the Riverdale Isolation Hospital (front).

Postcard to Anne’s best friend, Mary W (back).

A nurse, too, had taken pity on me and had arranged against the rules for the first giraffe to be sterilized so I could keep it after all. So when I finally arrived home by ambulance, since we had no car, I was the happy owner of three stuffed giraffes, obviously a family (a misapprehension which I would realize only much later when I went to Africa). These giraffes and other toy animals were the stars of a grade 8 too-long presentation made by my best friend and next door neighbour, Mary Williamson, and me on the habits of five mammals.

From left to right: Donald (standing), Hugh, Mary, Anne, mother Mary.

Anne’s father, Harold Innis.

I grew up in a middle-class family, youngest of four children, with a professor of economic history for a father and a writer/homemaker for a mother. My father, Harold Innis, seemed to me perfect -- never angry, full of jokes, but so engrossed in his academic work that he had little time for home life. For Christmas he went into Albert Britnell's bookstore on Yonge Street and bought everyone books as presents; mine were always about animals.

Anne’s mother, Mary Quayle Innis. Dean of Women, University of Toronto, 1957.

My mother, Mary Quayle Innis, took child-raising seriously, arranging all sorts of cultural activities such as original plays, the making of puppets from paper maché, photography experiments, and piano lessons for the two girls, which I suffered ungraciously, but not for the boys. She resented having to spend so much time on housework when she considered herself a writer. However, such work and her children inspired many of the articles she wrote for Saturday Night and later the United Church Observer. Her only novel, Stand on a Rainbow (1943), was a classic in its depiction of middle class family life in Canada. Although she was an English major from the University of Chicago, urged on by my father she published An Economic History of Canada in 1936 because he needed a basic text for courses he was teaching. This also was successful, serving many generations of undergraduates until fairly recently. Her other books included histories of the YWCA and of nursing in Canada and a study of early Canadian explorers.

The highlights of our family life were the two-month summer holidays we spent most years at Footes Bay, Muskoka, in a rented cottage. This would have been an ideal place to study nature, but no one I knew was knowledgeable in the plants or animals around us. My mother recognized a few birds (cardinal, tanager, goldfinch) and loved flowers, but that was all. When I was 12, a boy told me that a certain duck was a mallard; I had never known before that ducks came in many species. I thought all ducks were the same. At that time birders were rare and usually men -- the Toronto Ornithological Club, for example, did not admit women.

(l to r) Anne and Mary W., 1945.

My childhood friend, Mary Williamson, and I had the choice of going to a public high school, Oakwood Collegiate, several miles away from where we lived on Dunvegan Road, or to the private The Bishop Strachan School (we had marks deducted if we left the "The" off the school's name) which was in the next block. We chose the latter, fortunately, because it is now well-documented that girls do better in science and mathematics in all-girl classes.

(l to r) Anne playing lacrosse with Mary W., 1947.

I spent five wonderful years at B.S.S., still determined to study the giraffe in Africa as my life's goal. However, I did not take a biology course there on the principal's advice because I needed physics and chemistry if I wanted to take biology at university. My energies went to sports, which I had not been exposed to at Brown School beyond skipping at recess and a few games' classes. I loved all sports -- "using up energy" being an important criterion for me. I won a badminton cup at doubles, played hockey and lacrosse, skied at Summit near Richmond Hill or Collingwood each winter weekend, made the school basketball team, started tennis and my final year came first at Sports Day. I was captain of the sports team Gamma, runner up for School Sports' Captain, and winner of School Colours.

Because B.S.S. was an all-girls' school I didn't think much about boys. When my family teased me about a possible boyfriend when I was 15, I dropped him immediately. When a friend called me a "woman" five years later, I was upset. Women, for me, were obviously people who didn't do very interesting things -- I certainly didn't want to be thought one of them. I planned a more exciting future for myself than women had. The only role model I recalled reading about at that time was Helen Keller, introduced at Girl Guides, a person whose attributes I did not want to have to emulate.

(l to r) Mary W. and Anne. June 28, 1950.

When I was 18, I wrote for the annual B.S.S. Yearbook that my ambition was to play on the Canadian Davis Cup team. I didn't understand when a friend said the competition was only for men. I found it impossible to believe that the sex of a person could matter in an event of such importance. Granted, I had never known of a woman who played for the Davis Cup, but I assumed this was because so far no one had practised as hard as I intended to practise.

As I pondered going to the University of Toronto to study biology, I worried about whether I could bear to dissect a rabbit which had been killed so I could work over its innards. My brother Donald finally persuaded me that it would be an old rabbit which was going to die anyway, that it would want to be of some use to human beings. This is still an issue that worries many young women and keeps some of them out of biology. Later, in a physiology lab, I was appalled when my lab partner killed a fish with a knife so we could examine its blood in a microscope. We didn't need to do this -- the text had a picture of fish blood far better than anything we saw.

“I was asked to hold rats while liquids were injected into their stomachs, a process I found so upsetting...”

For two summer jobs after leaving B.S.S. I worked as a slide cleaner in a histology lab at the Banting and Best Institute. The salary was a mere $20 a week yet the work routine but interesting because I learned how tissue slides are made and stained. I was embarrassed when told that a tissue I did not recognize was testes. During my second summer I was asked at one point to hold rats while liquids were injected into their stomachs, a process I found so upsetting I could not eat my lunch and had to be excused. One day I watched Sandy Best, son of Banting's colleague Charles Best, do an experimental operation on rats involving sewing glass containers into their abdomens. I found such research disgusting. At that time researchers were experimenting with by-pass blood techniques on dogs. I returned to the lab one Saturday morning to watch an operation in which one of the tubes broke away from the anesthetized dog, spewing blood over the researchers and the room. Those present felt we were watching history being made, which in a way we were.

About this time (1951) there was much discussion about hazing events at university where, each September, new undergraduates were forced by older students to do silly or degrading stunts. Rarely, new students were injured or killed. The thought of hazing so frightened me that I decided perhaps I wouldn't go to university after all. I final resolved to be brave because non-denominational University College where I registered had largely apathetic students who, it was generally held, were unlikely to have much of an orientation program of any sort. This proved to be true although I had to wear a Freshie beanie on my head for several days.

“I distrusted adults and the hierarchies they imposed — as I grew up they always seemed to be thinking of ways in which my ideas wouldn’t work, rather than wanting to discuss or try to implement them.”

Later on while at university I felt my privacy was again invaded each winter when I, along with all other University College female students, had to have an interview with the Dean of Women and supply a bottle of urine for some medical assessment. I always put off these two annoying and irrelevant requirements as long as possible. I distrusted adults and the hierarchies they imposed -- as I grew up they always seemed to be thinking of ways in which my ideas wouldn't work, rather than wanting to discuss or try to implement them. I remember being verbally chastised because during registration in first year I said I was enrolling in the "Science" program rather than in "Honour Science," which seemed to me a too elitist title.

First year university was a whirlwind of activity. I wanted to be involved in everything that university had to offer, even though I had 35 hours a week of lectures and labs. I ran for and lost the election for first-year woman representative of University College, I tried out for the university basketball team which seemed already to have been covertly selected since no one ever watched me play, I tried out for the university tennis team for which team I later played and received a Senior T award, I played ice hockey for the college, and I joined the campus newspaper Varsity staff as a reporter. My journalistic career was brief, with a single assignment to interview the university registrar, Dr Evans, on a matter which had already been thoroughly covered and which we both soon realized was a waste of his time and mine.

The academic timetable was horrendous. Honours science students had to take three-hour afternoon labs in all the sciences and since chemistry demanded two lab periods, geology was held on Saturday mornings. The chemistry labs involved endlessly weighing, reheating and weighing again chemical substance of unknown provenance in a crucible to obtain a constant weight. Weighing balances were shared between two students; one had to wait while one's partner shifted a tiny piece of metal on the balance, then watched the weight pendulum slowly swing back and forth five times to be sure the swings were equally broad to the right and to the left. If they weren't, the metal "rider" had to be moved slightly and the pendulum swings noted again. After weighing the crucible to four decimal points, one heated it in an oven where it jostled with dozens of other crucibles and hoped it didn't spill before being reweighed. It is amazing that anyone went into chemistry after suffering through this boring and almost pointless exercise.

Geology, by contrast, was wonderful. The professor was the well-known Dr. Arthur Coleman who centred each lecture around slides. Sometimes he'd turn on the lecture-room lights suddenly to surprise those who were sleeping, but I found his descriptions and illustrations enthralling. The Saturday-morning lab was less exciting, focused as it was on learning to identify different kinds of rocks for identification quizzes. There were only single samples of the rare specimens, so we memorized their accession numbers rather than worry about their other characteristics.

Physics experiments were one-of-a-kind, so that pairs of students spent each week writing down results and preparing reports on a different topic such as acceleration due to gravity (Fletcher's Trolley), harmonic motion (swinging ropes) and Archimedes' principle (tubes and pans awash in water). Each student had to make a thermometer, first blowing a glass bubble at the end of glass piping, then filling it with enough alcohol so that when heated it rose a reasonable height in the tubing, and finally sealing the tubing before the alcohol boiled out of it. The number of thermometers broken by careless classmates and burns sustained by flying alcohol necessitated a professor attending constantly in the thermometer room where we went to work in our scant free time. This professor was usually Miss Allen, a minion of some sort we presumed because of the work she did in drying tears and encouraging those in despair. It was much later that I found out that Miss Allen had a PhD and was every bit as qualified to be a professor as were her male colleagues, who were called Professor or Doctor. However, she was obviously marginalized by them and given the most unpleasant and footling jobs. Despite such discrimination, there were more women then on the physics faculty than there were later.

Anne (top row, second from left) with fellow students, 1954.

The botany labs were more straight forward, involving drawing and labelling plant parts and making diagrams of life cycles. We took this course with first-year foresters who were all men. One forestry acquaintance came over to chat with me once while I examined the cross-section of a tree trunk. Immediately his classmates sent up a buzz of comment because, as he explained, he was fraternizing with the enemy. He soon returned to the forestry side of the room and the commotion quietened down. I was reminded of this incident in 1982 while on a coach-camping trip of Australians through the Queensland outback. Usually, except for couples, the men and women kept to themselves which was not easy when 48 of us were always crowded on the bus or at the lavatories (Jackaroos and Jillaroos) or in the campsite. When I sought a hunter out one day to ask him about the distribution of water buffalo, the other women watched in amazement. Later they demanded to know why I had been "chatting up" that man.

The labs in zoology centred also around drawing and labelling, this time of animal parts. On the first day we had to draw the internal anatomy of a worm using a low-level microscope. Our textbooks gave illustrations of the stomach and other organs we should be seeing, but none of these was evident to me in the murky brown lumps that appeared in the microscope. The lab demonstrator urged me not to worry -- I should just draw what I saw and label what I could recognize. I took his advice, which resulted in a fuzzy long object on the page barely elucidated by four or five labels (skin, internal organs, anterior end, posterior end). I received a D for this effort. From then on I did what the others did -- copy the text's drawing with a few unimportant changes to reflect original work. These drawings all received As or Bs.

As well as the five basic sciences, Honours Science students were required to take courses in mathematics, English, French and an elective to keep our interests broad. The one-hour-a-week electives as I recall, were military history, religious studies, or Greek and Roman history, which I took.

During the next three years I took courses as prescribed, ending in fourth year, for a change, with mostly electives. Only a few of these early courses stand out in my mind. One was a course on eleven novels taught by Prof. Priestly. All were long (Dickens, Eliot, Richardson) and all were to be read during the year which I found absolutely impossible because of lack of time. Luckily the class at University College was large enough so that Priestly did not know our names. When he asked a question, he had to catch someone's eye to get the answer. The result was that most of the class spent each session not cogitating on literature, but trying to remember not to look at the professor.

The class that illustrated memory block for me was scientific German. The second World War had been over less than ten years and I found my resistance to the subject matter high. It was impossible to remember what I learned in class. When I looked up a word in the dictionary, I forgot it again immediately if I hadn't written it down. I finally passed the course with a D after writing the supplemental exam.

Biochemistry in third year completed my disaffection for chemistry. For a mid-term we were required among many other things to know Kreb's cycle, in which eleven complicated chemicals give off or take on other chemicals and units of energy. I decided that the principle would be all that was required-- the thought of memorizing in sequence eleven organic compounds showing the conversion of acetyl coenzyme A to carbon dioxide was too awful. But of course that was what was required and I received a terrible mark in the test to remind me. This professor also asked that we go to the library and look up “the literature” on certain chemicals. We were all bemused at this. What was “the literature”? We had thought that all knowledge was in our large textbooks.

The most useless course was embryology, which bored professor Coventry as much as it did the students. The highlight was the professor's ability to draw two large circles on the blackboard at the same time, but this excitement did not last long. In the lab we had to carry out a project that interested us, which was difficult to find. I chose a busywork one of tracing the enlarged outline of one organ from successive slides of that organ so that I could eventually build up a three-dimensional model in which no one was the least bit interested. What a waste of time.

The most agonizing course was that of plant taxonomy for which each student had to hand in a fully-labelled plant collection of 100 species. The prospect of picking 100 plants complete with roots and flowers and keying out their glabrous and other characteristics was so daunting that I put it off as long as possible, figuring that if I caught some terminal disease at least I wouldn't have wasted precious time before I died. By fall, the few spring flower I knew were largely gone to be replaced by asters, members of a highly complex group. I spent months trying to identify my miserable specimens, first failing to succeed with Gray's Anatomy and then guessing wildly from a variety of coloured pictures in field guides.

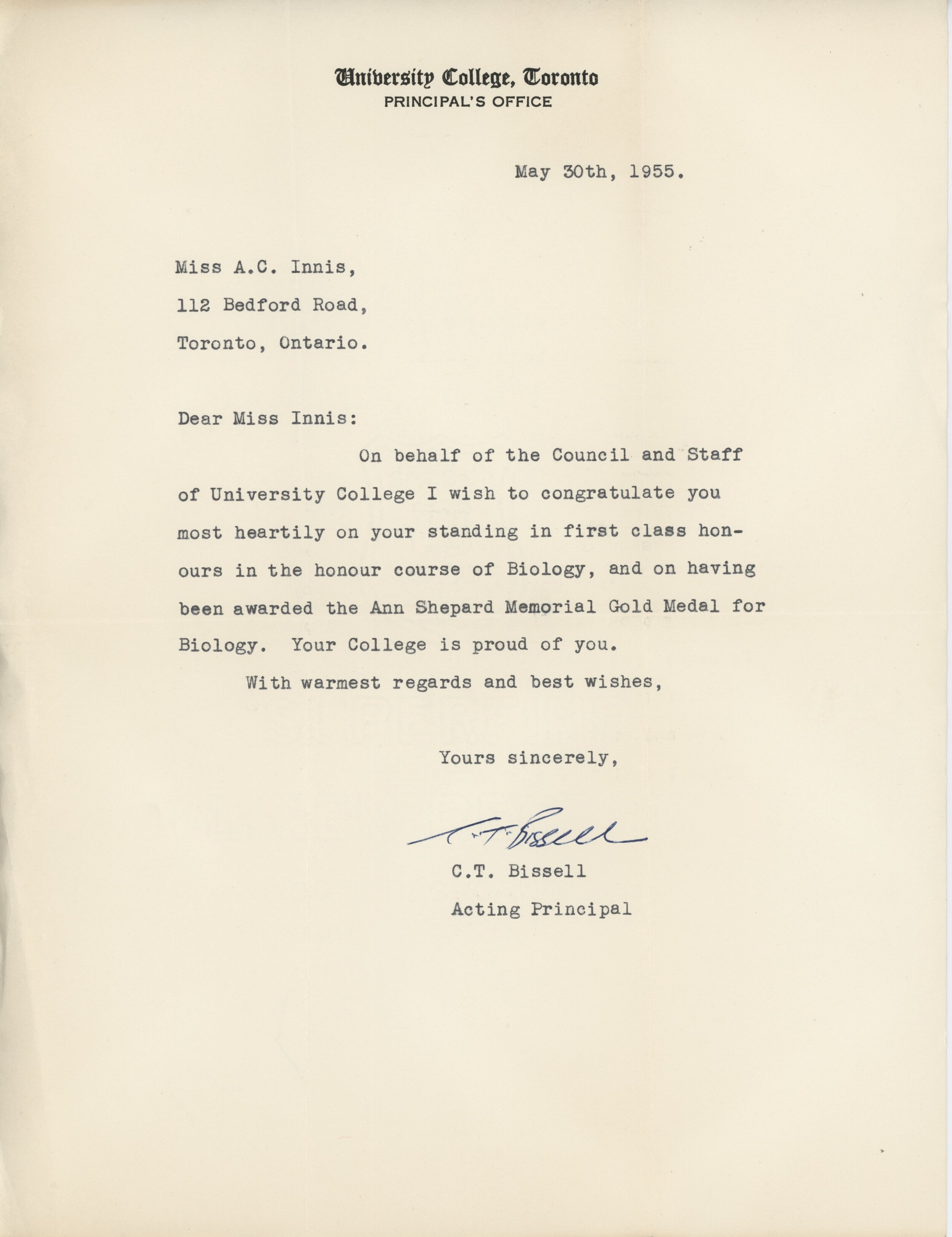

Ann Shepard Memorial Gold Medal for Biology.

It has been well documented that women (but not men) in general enter university with a higher self-esteem than when they leave it four years later. This happened to me, too, even though I entered the University of Toronto with a B average (too much sports at high school) and graduated with the Gold Medal in biology. I learned a great many things at university, but confidence in my own ability wasn't one of them.

On thinking back over my undergraduate career, a number of incidents probably caused my loss of self-esteem:

* There was a university-wide competition to see which women could fit into a life-size cardboard shape cut out to represent the silhouette of the Venus de Milo. I knew I was too fat. The ones who did fit were all popular and often girlfriends of the BMOC (Big Men on Campus).

* Men I worked with part-time at the Royal Ontario Museum routinely came to the lunch-time University College women's hockey matches to shout and laugh. Granted, our team wasn't very good, perhaps in part because our practise time was from 7-8 a.m. at the Varsity Arena, which meant that many of us had to be up before 6 and lug our skates and socks and slack and jackets around during the day. (I never wore slacks to class -- that would have seemed disrespectful. Nor were slacks allowed in the residences' dining rooms). Our team never scored a goal in four years. But that grown men would make our incompetence a source of high amusement so that we could hear them whooping and shrieking with merriment at our mistakes is astonishing. At the time their teasing left me mildly depressed, but I wasn't sure why.

* One afternoon on my way to the library I was stopped by an engineering student who said that for his orientation he had to kidnap me and take me into the nearest building. He was apologetic but strong, because I couldn't escape from his grip on my arm. We both therefore walked into the medical hygiene building, where I stopped and asked him "What now?" He didn't know so he released me and I carried on to the library. This incident was irksome at the time, but now would be genuinely frightening.

* Each summer, my male classmates were hired to work with Dr. R.L. Peterson in collecting and preparing skins of small mammals from across eastern Canada. They drove a van all summer, stopping each night to trap specimens which they prepare for research the following morning. This was valuable experience for would-be mammalogists, among whom I counted myself, but women were not allowed to take part in such field trips. One of our projects in third year was to collect a series of "sig obs" (significant observations) from nature; the four girls (of nine in total) in the class were disadvantaged in this as none had a job in natural surroundings.

* Several summers I applied to be a fire ranger in northern Ontario, but again women were judged unsuitable for such jobs and never hired. Instead, I worked at the Royal Ontario Museum cleaning mammal skulls with tweezers for much less money.

* One summer I also worked on a project for Dr. Peterson measuring each red fox skull in 19 different places so that a graduate student, C.S. (Rufus) Churcher, could later use these data to work out possible races of this species. I enjoyed the work because at last I was dealing with actual specimens involved in actual research. However, I felt self-conscious because it seemed an odd job for a "girl". When people asked me what I did, I said I worked with "fox skulls" in such a rushed manner that several thought I had said "fossils" and inquired further about what I did with these fossils.

“...an older man in the year ahead of me said that my future should be as a mother because I had wide hips. I was appalled at this comment which negated everything I was working for.”

* One day, an older man in the year ahead of me said that my future should be as a mother because I had wide hips. I was appalled at this comment which negated everything I was working for.

* At the field camp in Algonquin Park which was part of our course I was equally appalled while walking along the path one night when a professor came up behind me, put his arm around my waist and pulled me toward him. I immediately broke away and ran in the dark to the "girls" cabin. After that I avoided going to the area where that professor had his office. I never told anyone about this.

* At a seminar in mammalogy I was the only woman present and subject to many sexual innuendos as the class of eight worked over skins and skulls on the fourth floor of the Royal Ontario Museum. Gays were fair game too; I remember one man wondering exactly what gay men did together. I had never heard of gay men.

* In that course I had to give a paper on colouration in mammals. As I presented my work I came to the word "zebra" hyphenated at the end of a line. I was immensely embarrassed to find "bra" by itself at the first of the next line and stuttered in confusion. At that time the word "pad" was similarly nerve-wracking because of its connection with menstruation. I never used it and blushed when others did, even when it referred to where hip people lived.

In retrospect the loss of my self-esteem, which had been high when I entered university, was evident in a class presentation I gave in my fourth year on the gaits of Peripatus, a centipede- like invertebrate from Africa which was believed to have evolutionary significance and which I would later see in Africa. My speech was based on a single paper which I had studied thoroughly, but I was so tense that for the full half-hour as I talked my voice shook uncontrollably. I was mortified at this display of nervousness, but could do nothing about it.

Other memories indicate how unworldly some of us were. Sometimes I went with Robert Bateman, now a successful painter of wildlife, to sports events followed by a dance at Hart House. We once watched two young males wrestling, one of whom had a small tear in his shorts. When Bob asked me later if I had seen the hole, I said no, which must have sounded ridiculous as well as untrue. On another occasion when I was with Bob, a comic performer said as part of his spiel "Voulez-vous coucher avec moi ce soir?" which I pretended not to understand because the implications were so horrendous. I went out with my first long-term boyfriend for six months before I let him kiss me, because an Anglican priest at high school had told us we shouldn't kiss a boy until we were engaged. Perhaps I was one of the few who believed him.

I continued to try to expand my interests as much as possible while at university. Once I went to the basement of University College to attend a lecture on Baha’i, but when I reached the door of the lecture-room I saw several men with beards inside; this unnerved me so that I decided not to stay. I always attended special lectures in biology, wanting in this way to keep in touch with new, cutting-edge research.

During the summers while working at the Royal Ontario Museum I started using the museum library to collect information on the giraffe. That available was largely anatomical, from early scientific journals. There was little on behaviour beyond anecdotes recounted by hunters or explorers, so I was delighted when I came across an assessment of the intelligence of the giraffe. This stated that the giraffe, like the cow, had 25% of full intelligence. I copied this fact down to Dr. Peterson's hilarity when he saw what I had done. "What does that mean?" he laughed. "What is full intelligence? How was it measured?" When I thought about it, I saw why he laughed. I realized for the first time that just because something appeared in print didn't mean it wasn't foolish.

Anne Dagg, graduated from the University of Toronto, 1955.

I graduated from Honours Biology in 1955 with the Gold Medal for scholarship, but I had learned little about the giraffe during my four years of study. Nor did my new degree open any doors toward going to Africa to do field work. I wrote to a number of people to ask about ways and means of studying giraffe in the wild, including L.S.B. Leakey who would later help various women study wild apes, but no one was encouraging. They offered instead reasons why I couldn't and shouldn't come to Africa -- a "girl" wouldn't be able to do so alone, the rhinos were too fierce, there was no money for such a study and no interest either.

Because of my lack of success, I finally enrolled in the masters' program at the University of Toronto to study the genetics of mice so that I would not waste a year. My interest in genetics had been stimulated by the excellent teacher Dr. Len Butler. My father had died by this time, but my mother, then the Dean of Women at University College, kindly agreed to help finance my further study. I took several courses in zoology, demonstrated in a undergraduate lab to earn money, and worked on my thesis -- a study of the differential nutritional use of various foods by five races of mice. I weighed newborn mice by the thousands over a period of many months. This was one of the few thesis topics that did not involve hurting live animals in some way.

At my master's oral in the spring of 1956 I was much less nervous while presenting my findings than I would have been a year earlier. I was pleased to be able to share my results with my thesis committee members who were supposed to be involved in my research. Only most weren't. They listened to what I had to say, then asked a few picky questions they had thought up on the spur of the moment. I wasn't even sure that some of them had read my thesis. One professor's only questions went like this:

"Are grey squirrels carnivorous?"

"Yes, sometimes."

"Why do you say that? You're right, of course."

"Because you wouldn't have asked the question if it hadn't been true." Some laughter.

"I have no more questions."

The only member besides Dr Butler who had gone over my thesis in detail was Prof. Norma Ford Walker, a human geneticist and rival in the department of Prof. Butler. She had cornered me a few days earlier to show me that I had used the wrong statistics in my analysis. I could only reply that I had used the statistics specified by Butler. I felt confident these were suitable because Butler taught several full-year courses in statistics which I had taken. Walker brought up the issue of statistics again in my oral exam, and insisted that I agree with her that I understood where I had gone wrong. I was worried, and pretended not to understand what she was saying. After several minutes of feigning ignorance, my supervisor, Butler, came to my defence. The exam ending with a fierce argument between Walker and Butler which the chair suggested should be finished elsewhere. I passed the exam, but was disillusioned with academic discourse.

Although I had written up my work into an acceptable thesis in zoology, it never crossed my mind that my results might be submitted as a paper to a scientific journal. Nor did my supervisor nor anyone else suggest this. I suppose it did not occur to them that I might really envision a career in zoology for myself despite my declarations of wanting to study giraffe in the wild.

“...looking back on these years in science, it seems appalling that some professors made so little effort to make their subjects interesting.”

On looking back on these years in science, it seems appalling that some professors made so little effort to make their subjects interesting. Science should be a turn-on for those interested; instead, it was often an incredibly boring exercise in memorization and busywork. Nor did much change later. Sheila Tobias (1990*) studied science pedagogy by having intelligent non-scientists take introductory science courses in 1987 and comment on the experience. They were unimpressed with the large impersonal classes, the endless problem-solving approach, the competition among the students, and the lack of context for what they were learning. She surmised that science professors don't necessarily see their job as captivating students. The professors give the students the facts that they should know; the students, who plan to be scientists no matter what, set themselves to learn these facts and don't need any other inspiration. The students who don't like this approach may drop out, but no one is much worried about them as it is assumed they wouldn't have made good scientists anyway. (* They’re Not Dumb, They’re Different: Stalking the Second Tier).

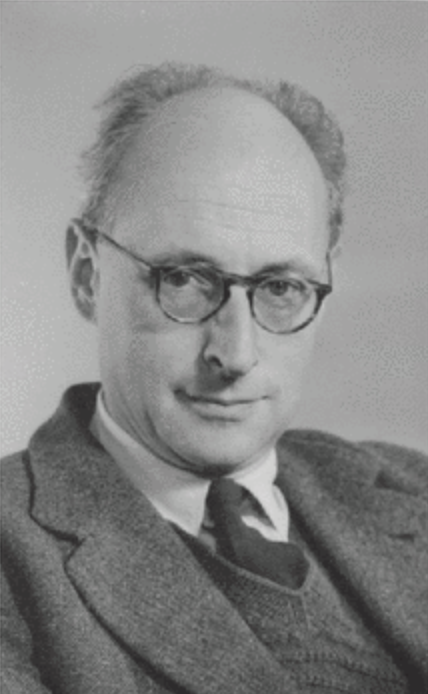

Professor Denis William (Jakes) Ewer, invertebrate zoologist and physiologist.

During my master's work, a fellow graduate student (later a University of Toronto professor) Rufus Churcher told me about two of his earlier professors now in South Africa, Griff Ewer and Jakes Ewer; he said they were originally from Britain and might be able to help me. I contacted them and Jakes put me in touch with a farmer in the Eastern Transvaal who had many giraffe on his ranch as well as cattle and citrus trees. Using my initials rather than first name so he wouldn't know I was a "girl", I wrote to this farmer who invited me to stay on his ranch and undertake my research there on the behaviour of the giraffe. He wrote that I could stay with the other cattle hands. I was ecstatic and arranged to leave for Africa as soon as I had completed my master's degree.

Telegraph to Anne from Mr. Alexander Matthews.

I arrived in Grahamstown, South Africa, where the Ewers taught at Rhodes University, in the summer of 1956. The Ewers had no real idea of who I was, but they treated me with kindness by giving me full board for my first week in Africa. At dinner on my first evening, the cook made stew which was delicious. Unfortunately, because I was nervous, when I tried to cut a piece of meat on my plate my knife slipped, dumping half the food into my lap. It was hot and wet, but since I was wearing an Innis tartan skirt which might hide this disaster, I felt it best to pretend nothing was wrong. I spent the meal surreptitiously returning bits of potato and carrot to my plate and sopping up gravy. The others must surely have noticed this mishap but they were too polite to say anything.

Anne and her Ford Prefect “Camelo”.

In Grahamstown, to my horror, the second letter I had from Mr. Matthew from his giraffe ranch, Fleur de Lys, stated that he had to withdraw his offer of support because he now realized from my second letter that I was a "girl". He was sorry that I had needlessly come so far, but was sure I would understand that he had no place for me, since his wife and daughters were out of the country and I would have had to stay at his house. I wrote back begging him to reconsider his refusal -- I could stay in a nearby hospital, or in a tent, or even in my new-to-me car, a Ford Prefect I called Camelo (for the generic name of the giraffe, Camelopardalis) which I bought second-hand for £200. Finally, Mr. Matthew changed his mind and decided I could stay with him after all, to give me a chance to accomplish my dream. He had been worried about the propriety of living in a house with a young woman, but since he was 57 years old and I was only 23, this seemed to me a bit ridiculous.

Alexander Matthew.

Parkland giraffe at Fleur de Lys.

I set out early one morning in my car to drive the thousand miles to Fleur de Lys, even though driving alone along rough dirt roads in the countryside was felt to be dangerous. I was told to take four days for the trip, but decided I would drive for 16 hours each day and make it in two. My car finally broke down but by then I was within a few miles of the ranch and decided to walk along the deserted road in the pitch blackness of night, scared almost out of my wits of snakes and leopards and drunken men. I was infinitely relieved to reach the ranch and meet Mr. Matthew who was to prove kindness itself.

Anne wrote all of her notes on giraffes in “Scribblers”.

Anne’s first giraffe entry, September 5, 1956.

I studied the ecology and behaviour of the 95 giraffes on the ranch for six months, strongly supported by Mr. Matthew who loaned me his movie camera and bought as much 16 mm film as I needed to film the giraffes' activities. Mr. Matthew was determined that I should get as much out of my stay with him as possible. Each morning, seven days a week, he knocked on my door at five a.m. and left a cup of tea so that I could study the giraffe for two hours before returning for breakfast with him and the man in charge of the orange orchard. I continued research until noon, and then again in the afternoon until it grew dark about seven. Then we had dinner also prepared and served by Watch the cook. From eight until nine, Mr. Matthew and I sat in the parlour, Mr Matthew chatting about his past and the history of the Transvaal while I fought desperately to keep awake. On Sundays, Mr. Matthew came into the field with me so we could take more films of the giraffe. Some of the footage of sparring matches between males was bought many years later for a WNED television documentary on giraffes.

Bella (left), 13, and her brother Enoch, 6, loved to sit on the running boards of Anne’s car.

Mr. Matthew had one set of friends in the neighbourhood whom we visited sometimes for dinner. Otherwise, he kept to himself. His neighbours kept their eyes on him, though. One man, when he met me in the one-room store at nearby Klaserie, would ask me how my "husband" was. I never knew what to say to this.

Another ranch family asked me over once for tennis on their home-made gravel court on a day Mr Matthew had driven to town. They warned me to be careful when I retrieved out-of-court balls (the nets enclosing the court were not high) because there were black mambas about whose bite is lethal. This family was so excited to find I was a good tennis player that they asked me to come to a tournament with them the next weekend, 150 miles away, which I was delighted to accept. (They thought nothing of travelling so far for a match). It would be a real change. However, when I told Mr. Matthew about this plan, he vetoed it. He said I hadn't come to Africa to play tennis, so I must refuse to go, which I reluctantly did.

On a second occasion, when I was again visiting this family for dinner, seven of us crowded into an old car to search for lions which were killing their cattle. The father drove slowly around his property while we all peered into the darkness. After a few minutes we spotted a large male at which the father shot from his window; lions were considered vermin, so there was no notion of sportsmanship involved. At the gun's retort the lion immediately leapt away, leaving a few spots of blood, and we were unable to find him in the dark.

By this time everyone in the car was greatly excited. We arranged to meet the next day at breakfast to track the lion down. This time we drove in a truck, where the women and several children huddled hoping the lion wouldn't leap in among us. We parked where we had last seen the lion, then watched the Africans track its spoor, followed in turn by four white men with guns. They found the animal dead beside a tree after an hour or so of growls, many gun shots and then unnerving silence for those of us left behind. Later the father gave me one of the lion's small bones as a memento of the experience. When I asked what bone it was, he said vaguely it came from the thigh area which I found puzzling, because I had studied cat anatomy at university and I couldn't recall a small thigh bone. I realized later it was the penis bone; the men must have had a fine time joking about this gift for the girl from Canada who called herself a biologist.

Giraffes in South Africa.

For three months during my stay in Africa I visited east and central Africa to observe giraffe and giraffe habitat there. I worked briefly as a typist in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika (now Tanzania) to replenish my finances, then travelled alone overland by train and bus to Arusha and Nairobi and by foot with African porters and a guide up and down Mt Kilimanjaro. Later I headed south by bus, ferry, train, car and plane by way of Kisumu, Lake Victoria, Nyasaland and Southern Rhodesia. At Umtali, where I met Mr Matthew who had driven north and wanted a holiday, we drove to Zimbabwe ruins and to Victoria Falls where we flew in a small plane over giraffe in the Caprivi Strip. I returned to Fleur de Lys with Mr Matthew to make further observations on giraffe and finish the film we had been producing.

When I had completed my behavioural and ecological observations on giraffe, I wrote them up and added what little had been documented by other writers to make a lengthy report on the species. When I sent this to Griff Ewer, the mammalogist who was later to write The Mammals and The Carnivores, she wrote back to explain that in a scientific research paper one included only one's own original work. I had never realized this before. When I had rewritten the paper, I sent this shortened version to the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London in which much of the earlier work on giraffe had appeared. It was immediately accepted and published (Innis, 1958). When I reread this paper today I am horrified at my description of a giraffe family, shades of my scarlet fever days when one giraffe had a blue ribbon, one of pink, and the third was a young animal, obviously their offspring. Now we know that families are not nuclear in most species, certainly not in the giraffe, and that a female giraffe will mate with any male that appeals to her when she is in heat.

“This paper represents, to me, a determination to gratify an ambition which would have been considered impossible by many people.”

I was so immensely proud of this paper that I sent copies to a large number of friends and acquaintances. Professor C. David Fowle wrote back "This paper represents, to me, a determination to gratify an ambition which would have been considered impossible by many people. I recall the amusement with which your announcement of your intentions was greeted by your friends a few years ago. You now have the last laugh, and in the distinguished company of Harrison Matthews too!" My goal of doing research on the giraffe was well known during the years I was growing up. People probably thought such an ambition was cute. But no one ever sat down with me to explain that expertise on giraffe was not a career. When I had realized my dream and returned from Africa, I no longer knew what I was supposed to do beyond writing up my work. My future seemed blank. Had I been a man, I'm sure my lack of realistic planning would have been discussed openly.

Anne and Ian, 1950s.

Wedding Announcement.

While in London on the way home by boat from Africa, I married a Canadian physicist, Ian Dagg, and went with him on a wonderful honeymoon to Scotland, Denmark and Paris before returning with him to live in Ottawa. My mother at this time lived as Dean of Women at University College in two rooms at the university so there was no place for me to return to Toronto otherwise. Before we sailed for Canada I was asked to show my giraffe film at one of the monthly Zoological Society of London meetings, but our ship left too soon for me to be able to accept this offer.

Professor Rosalie (Griff) Ewer, Zoologist, Rhodes University.

When I first met Griff, she had asked me where I had published my master's research on the genetics of mice. This question made me realize that the point of research was not just to earn a degree, but to add information to the scientific literature for others to use and build on. Publications would also help build up one's career. With this in mind, when I returned to Canada in the fall of 1957 I wrote up my MA thesis work in a paper on how the genetic inheritance of mice affects their ability to utilize food and sent it to the Canadian Journal of Zoology. This journal accepted the work, but wanted a few changes made. The editor asked me to examine my graphs through a reducing glass and to use a ruling pen and lettering guide on Strathmore single or double ply drawing paper. I had no idea what any of these things were. These instructions, although entirely reasonable, so intimidated me that I gave up hope of having the paper published. Why I didn't ask my new husband to help me with the revision I cannot fathom. Perhaps I was afraid that he would laugh at my aspirations to be a real scientist?

When I returned from my year in Africa and visited the University of Toronto, I met my former supervisor in the hall. He greeted me as Miss Innis, then passed on. When I saw him again later in the day, he apologized for having called me by the wrong name. He had not known that I was married. He didn't ask about my research in Africa, which seemed to me of far greater interest.

“I spent the fall working at a temporary job at Carleton University and in my spare time what I planned to be the definitive book on the giraffe...”

Once in Ottawa, I tried to find a job in biology but with no success. Neither of the local universities wanted to hire me, nor did the National Museum. I spent the fall working at a temporary job at Carleton University and in my spare time writing what I planned to be the definitive book on the giraffe, using the various libraries in the Ottawa area. One large monograph on the colouration of the various races of giraffe was in German. I could only borrow it for a limited period so I spent many days translating and copying it in longhand. Such an undertaking seems bizarre in this age of photocopying.

In January of 1957, I applied to earn a doctorate at the University of Ottawa. I had already inquired about doing one on human genetics at the University of Toronto with Norma Ford Walker from a distance. She had suggested that I come from Ottawa to Toronto to discuss this, but when I arrived at her house she made it obvious that there was no way she would help me. By making me travel so far, she was apparently retaliating for the contretemps during my MA oral thesis presentation. One Ottawa professor, geneticist Edward Dodson at the University of Ottawa, wanted a graduate student to learn the new technique of counting mammalian chromosomes; he suggested I look into this using tissue he had collected from the sternums of primates. I spent months macerating bits of tissue and peering at the results through a microscope, but with no real idea of what I was supposed to be doing. It is no surprise that I made no progress. I doubt if a male student would have been given such an impossible task. I did take a course in histology and earned money demonstrating in an undergraduate lab.

“I received $2,000...which I asked a financial advisor to invest. He did so, putting the entire amount in my husband’s name. He couldn’t understand why this upset me...”

With no possibility of earning a PhD, I worked during the next year as the Physical Education teacher for Elmwood Girls' School where my 100 students ranged in age from four to twenty. Besides this, I did all the cooking and housework for ourselves and two boarders who were friends of Ian, as most women did in those days. I received $2,000 for this year's teaching, which I asked a financial advisor to invest. He did so, putting the entire amount in my husband's name. He couldn't understand why this upset me, and why I insisted the money be returned to an account in my own name.

In 1959 we moved to Waterloo, Ontario, where my husband had taken a job as a physics professor at the new University of Waterloo. I continued to collect material for my book on giraffe and also had a chance to carry out, with the help of the chemistry department, the chemical analysis of leaves I had dried and collected from African species of trees and bushes which giraffe did and did not eat. I could find no correlation of taste with any chemical component (Dagg, 1959).

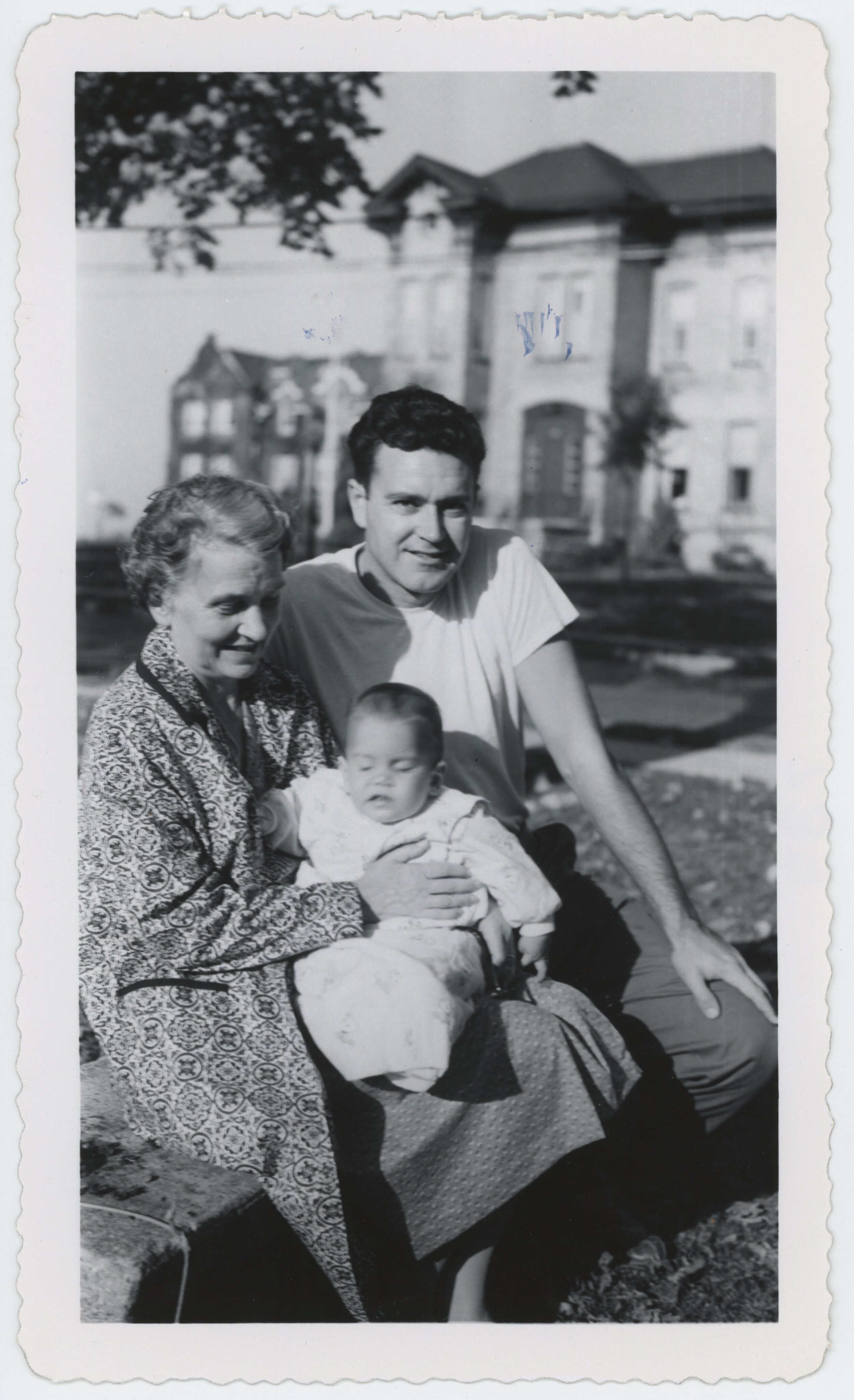

Mary Quayle Innis, baby Hugh and Ian Dagg.

Some months after my first child, Hugh, was born in March 1960, I decided to see if I could do research for some local agricultural group. I had been unable to find biological-related work at either the University of Waterloo or at Waterloo College, but I was sure I would have success if I agreed to work without pay. This way I would at least be able to keep my hand in at research. I called in at the Waterloo Pig Breeding Station to explain what I had in mind, but was greeted with at first disbelief, and then amusement. The manager had no work for me.

Slightly daunted, I decided next to offer my services to the Ontario Agricultural College at Guelph which was heavily involved in agricultural research. I visited a professor there, Dr. Rennie, to see if I could do volunteer research on cows. He gave me copies of his own research papers and references for others which I looked up and studied carefully. When I next visited this man, full of enthusiasm about a research project I had worked out which seemed feasible, he had no time for me. It amazed me that anyone would turn down my offer to work for him for free. It maybe amazed him that a woman would waste his time when she should be at home looking after her family.

Without any outside research to do, I turned again to giraffe, working on various aspects of the species to use later in the definitive book I was planning. One was on the unusual walking gait of the giraffe which was similar to that of the okapi, its closest relative; each spends a large fraction of each stride supported by the two legs on each side of its body while the others swing forward almost in unison (Dagg, 1960). Their legs are so long that this prevents the back leg from hitting the front leg during each stride. I had found this out by putting giraffe film I had taken in Africa into a slide projector and shining the image on a wall which I then traced. I noted which feet were on the ground and which were not in successive frames. I did the same analysis for the strides of an okapi I had filmed in a zoo.

“I’d be more likely to find a job and have papers published if people knew who I was.”

I realized by now (I was a slow learner) that contacts were important in the world of academia. I'd be more likely to find a job and have papers published if people knew who I was. I therefore asked if I could show my 20-minute giraffe film at the American Society of Mammalogists' 1961 annual general meeting at Champagne, Illinois. This was soon arranged for after the banquet. The showing of the film with my commentary to explain it went off well, but I was nonplussed to be introduced as "Miss Annie Dog" from Canada. To make three mistakes in a three-word name seemed a bit much. Had I known, it was a portent of the future, when I would find it almost impossible, no matter what I accomplished, to be taken seriously as a scientist. After all, I was a woman.

“This work at home with film meshed well with looking after a baby, so I elaborated the giraffe tracings I made...”

This work at home with film meshed well with looking after a baby, so I elaborated the giraffe tracings I made, adding the slope of the neck for the frames of each walking stride at varying speeds and for galloping frames as well. I found a close correlation between the movements of the neck and those of the legs of the giraffe in walking and galloping, its only two gaits, and also in its lying down, getting up, and jumping fences. My paper on the role of the neck in giraffe movements included graphs this time drawn with the correct pen on the correct paper (Dagg, 1962).

During this same period I was collecting everything I could find on the distribution and races of giraffe in Africa. This involved reading as many hunting, exploration and travel books as I could find. I also corresponded with many countries in Africa to obtain direct information on these characteristics. In 1962 I published papers on the distribution of giraffe in Africa and on their subspeciation (Dagg 1962a; Dagg, 1962b). In one old journal I had unearthed a detailed description in French of the arrival of the first giraffe to reach Paris, so I wrote up this adventure for a popular journal (Dagg, 1963).

“The male skulls had extensive bone deposits over the horns and around their base, presumably to enable them to take part in the sparring matches and more serious fights I had watched in Africa.”

I soon began collecting data on the weight of giraffe skulls stored in museums. When I had examined some at the Museum of Natural History in London, I had found that those of the males were far heavier than those of the females. The male skulls had extensive bone deposits over the horns and around their base, presumably to enable them to take part in the sparring matches and more serious fights I had watched in Africa. During these sessions males, never females, stood near each other and hit each other with their horns. By 1965, I had enough information including data from the Field Museum in Chicago to publish a paper on the topic (Dagg, 1965).

The first president of the University of Waterloo, Gerald Hagey, somehow heard about this effort, "Sexual differences in giraffe skulls," and never, in all the times we met over the years until he died, did he fail to mention it with a snort of laughter.

Anne with sons Hugh and Ian.

In the summer of 1962, when my now two sons were two years and several months old, I was asked to teach a course at Waterloo Lutheran University (now Wilfrid Laurier University) on the anatomy and physiology of human beings. I was delighted, especially when I was told the class would only have twelve students. By September the number of students had risen to fifty but I still enjoyed lecturing and running the labs I had prepared. In my enthusiasm for the subject I urged the students to do research projects of their own. They could test their cat, somehow, to see if preferred music by Bach to rock and roll. They could correlate their pulse rate with their activity level before and after eating. They could measure the diameter of hairs on their head to see if all were the same size -- knowledge useful for criminologists? They might even, I told them, want to write up their study and submit it to a scientific journal for possible publication. "Would the pay be good?" one man asked. I was as amazed by his question as he was by my answer: scientific journals not only don't pay for articles, they often charge the author for printing them. I realized by the students' hilarity that their mindset was different from mine. I taught this course again two years later and in the year between a course on comparative anatomy of vertebrates. For each year I was paid $3,000 for giving two lectures and a three-hour lab weekly for two terms.

Anne and daughter Mary.

“If someone else was in the house to look after the boys I could, by nursing her [daughter Mary] in my bedroom, gain four hours of quiet a day in which to study. ”

In 1965 the WLU Biology Department was expanding so I asked to teach a second course each year. This was acceptable, until I asked also that I be paid a full-time salary; this seemed logical as the two men in the department were full-time and teaching two courses and one course (several times) respectively. These men refused to allow a woman to join the department as a full-time teacher, so they hired a man to replace me, also with a Master's Degree but with less research experience. I was bitterly annoyed at this discrimination, and decided that I would have to earn a PhD if I wanted to continue the university teaching I loved. I therefore enrolled in the fall of 1965 for a PhD in biology at the University of Waterloo shortly after my daughter was born. If someone else was in the house to look after the boys I could, by nursing her in my bedroom, gain four hours of quiet a day in which to study. Dr Anton de Vos agreed to be my supervisor, even though he was a member of the Geography Department; he was a wildlife biologist who had just moved from the University of Guelph to the University of Waterloo.

The first course I was required to take was on natural resources in Canada. It was offered one evening a week so that external students from as far away as Oshawa could attend. The professor, my supervisor Anton de Vos, never bothered to prepare his lecture, but instead brought along a variety of books and articles to read from. Often he began a class with "Let's see now, where did we finish last time?" The best class was during the famous New York blackout of 1965 when all the lights went out; because he could no longer read to us, de Vos told us instead about his experiences in resource management, something he should have been doing all along. The classes were supposed to run from seven to ten o'clock but they often ended as early as nine; de Vos would announce that we'd worked hard and deserved a little time off, or that there was no point starting a new topic. The students who lived out-of-town were particularly irritated by his unprofessional behaviour, but no one complained officially -- if little material was covered, there would be little to learn and be tested on. Because de Vos still lived in Guelph, after each lecture he spent the night at my house.

The other course I took was on animal behaviour research, taught by Eric Salzen, a psychologist from Britain. I devised an experiment whereby a naive, newborn chick would or would not flinch when exposed to an expanding light shone on a screen in front of it. This was to be the first light the chick had ever seen, so the eggs were incubated in a closed container. I spent months designing the equipment and testing individual chicks, only to find that the incubator wasn't being kept dark at all. Whenever anyone else in the lab wanted an egg or a chick, he or she simply opened the container allowing light to flood in. I complained to the psychologist that the experiment was invalid and my time had been wasted, but he ignored my annoyance. I had hoped to become friends with this professor, the only local person in a field similar to mine, and several times babysat his children along with mine in the hope that he or his wife would reciprocate. They never did. He gave me a 74 for the course so I wouldn't have an A, given at the time for a mark of 75.

The other requirement besides a thesis for a PhD was facility in German. I had translated various articles from this language into English, but even so I was aghast when de Vos casually asked me to "Sprechen Sie Deutsch mit mir" to test my competence. Luckily I was able to persuade him that a written translation would be acceptable, so I did one of a German article about giraffe.

“I decided for my PhD thesis to study the locomotion of large wild mammals. By borrowing wildlife film from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and other sources, I could work largely at home while minding the children.”

After completing my film gait analysis on the movement of the giraffe's neck and legs, I had continued over the years to do research on gaits, using an 8 mm camera at every opportunity to film zoo and farm animals and different breeds of dogs. I decided for my PhD thesis to study the locomotion of large wild mammals. By borrowing wildlife film from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and other sources, I could work largely at home while minding the children. I organized a scheme whereby I could analyze sequences of individual animals walking, pacing, trotting and galloping and note which of their feet were on the ground in each frame. Since I knew at what speed the various films had been taken, I could tabulate the timing of the various supporting legs. After studying many thousands of frames of giraffe, pronghorn, and various species of deer and antelope, I was able to show that the way their four legs moved during their gaits varied with such things as size, shape, speed, and habitat. Deer, for example, have a very stable walk, with diagonal legs or three legs supporting the body during much of each walking stride. They live in fairly dense habitat, so they are able to spring away from danger at a moment's notice. By contrast, the heavy giraffe which lives in more open areas can manage with a less stable walk; it spends a large part of each walking stride on lateral supporting legs, either the two right or the two left.

During this graduate work I was unable to earn money, except by demonstrating in an undergraduate lab on vertebrate anatomy, because I had chosen a research area for which no professor had grants. I therefore had to watch my expenses carefully. Once I found that I could save a dollar if the $16 film of walking caribou I planned to rent were classified for educational use. I trudged a mile to the UW campus pushing the baby carriage to arrange this with the biology department, but was told that a graduate student's expenses somehow weren't educational so I couldn't take advantage of this saving. I trudged back home again, keeping my head down so no one would see my tears of rage. I never felt that anyone in the department wanted me to succeed, so this experience was not as unusual as I would have wished.

By late 1966, de Vos had made plans to leave the University of Waterloo. Although he had done me the favour of being my supervisor so I could undertake a PhD, he was little interested in my research beyond wanting hoof measurements to be considered in detail. I was eventually bogged down in reams of data on time during which each of the four legs supported each of the 25 species in each gait; age, sex and size of each animal; habitat type; and hoof characteristics of each species. I asked de Vos how to proceed but he was too busy or uninterested to help me, suggesting that my husband work with me instead. My husband had never taken biology, but he suggested a way for me to present the data which worked well.

My oral examination took place early in 1967. As with my master's oral, I found the examiners markedly uninterested in the topic of gaits; I'm sure several had not bothered to read all of my thesis. My external PhD advisor was Prof William Pruitt from Memorial University but we had never been in contact and he sent a list of questions to the meeting rather than attend himself. One examiner worried about a detail in one of the tables, one asked me to discuss the animal category Vertebrata, and a third wanted me to draw and label the parts of the vertebrate eye. Thanks to courses I had recently taught I could answer these questions easily, but I felt annoyed that my thesis topic was so little addressed. My results were written up in two papers for which I made de Vos second author in each, although he had had no input into them (Dagg, 1968a; Dagg, 1968b). I also published a note on the awkward gallop of the wildebeest which is a remarkably varied gait, with frequent changes of lead feet (Dagg, 1969).

“I had obtained my two graduate degrees in the minimum time possible, my MA in less than a year and my PhD in less than two. ”

I had obtained my two graduate degrees in the minimum time possible, my MA in less than a year and my PhD in less than two. Most people would consider this something to be proud of but, in the way women often have of doubting their own ability, I wonder if these short times were more a function of not being taken seriously as a scholar. The theses I wrote were made to seem unimportant and the awarding of degrees to a woman may have seemed unimportant too.

During winter and spring of 1967, I taught two term courses in zoology at the University of Guelph where de Vos had recommended me. The work involved was staggering; with only a few weeks' notice I had to create a new course in natural science for 160 arts majors which was supposed to broaden their perspective. The other course was four hours of lectures and six of labs each week on all forms of animal life from the amoeba to the cat for three zoology major students. I learned a terrific amount, but what with preparation at home, giving the lectures and labs, commuting to Guelph and back, and looking after three children under seven, I was exhausted.

Anne and her daughter, Mary, at the Taronga Zoo, Australia in 1967. (Note: in most Australian States, holding and cuddling koalas is no longer legal as it can stress the koalas. )

In August, 1967, our family took a sabbatical year's leave in Sydney, Australia. We lived up the street from the Taronga Zoo, so each morning while the boys were at school and my husband at work at the University of Sydney, I took Mary there in her stroller. Part of the time I was suffering from a kidney infection probably brought on by overwork at Guelph, but it was easier to get through each day watching animals than to sit suffering in the apartment.

Early in our stay, I visited the director of the zoo to see if he was interested in having research on mammals carried out. We discussed a comparison of the gaits of members of the kangaroo family, similar to what I had carried out for large hoofed mammals, but the director wanted me to wait until he had the various species housed in large cages. This was never done, so I filmed kangaroos and wallabies as well as I could anyway, before I left Australia. Several years later, I arranged for a graduate student, Doug Windsor, to film other species in Californian zoos so all the footage could be analyzed for his master's thesis. Together we wrote a paper called "The gaits of the Macropodinae (Marsupialia)," which was described in Nature (Windsor and Dagg, 1971).

I also worked on three other projects while I was in Sydney. The first was a quantitative description of the spotting characterizing the races of giraffe. I was able to work out the family tree of the 18 giraffe at Taronga by going through back issues of the newspaper Sydney Herald. Whenever a calf was born, there would be a picture of it in the paper, together with its mother. The spotting of each animal remains constant throughout life, so I could soon recognize the animals by name. The newspaper also gave racial or subspecific names for some individuals. I photographed the bodies of members of several races, then, using a planimeter, worked out the proportion of the area of spots to the area of background. The values I obtained varied depending on the race (Dagg, 1968).

A second study, "Tactile encounters in a herd of captive giraffe" (Dagg, 1970), involved watching the brief interactions between individual giraffe over the course of 66 days, the interactions including nosing, licking, rubbing, hitting, sniffing genitalia and sparring. I was able to generalize among other things that giraffe adults often touched young calves with their noses but calves only licked and nosed each other, that the males commonly sniffed the females' genitalia, that mothers nosed or licked their own young which often elicited suckling, and that the oldest male at 24 years was no longer involved in social contact.

Such details seem prosaic to most people, but I found it fascinating to try to work out the relationship between the giraffe of various ages and the two sexes. What made a giraffe touch some animals but not others? I felt that I should be able to figure out how the mind of a giraffe worked because of its behaviour, although in reality I was unable to do this.

On one occasion I watched the big male, Oygle, mount a receptive cow. I was in the processing of documenting this excitement when Mary, becoming bored, climbed out of her stroller. In desperation I thrust paper and crayons at her to buy time for my observations, but she quickly tired of these. Then I gave her my purse to examine which took a little more time and included her ripping up and discarding my driver's license which I realized later. Finally she wandered away entirely while I was torn between following her and completing my note-taking. Mary finally won, as I began to imagine her falling into the hippo pond or poking a stick at a lion.

“The need to divert Mary triggered the third study. She didn’t like to sit still for long, so each day we traced a circuitous route through the zoo to visit the greatest number of large mammals.”

The need to divert Mary triggered the third study. She didn't like to sit still for long, so each day we traced a circuitous route through the zoo to visit the greatest number of large mammals. On cool days most of the mammals would be resting or moving about in the sun; on the hot days they would stick to the shade. I decided to make a daily chart of sunny days noting the air temperature and how many individuals of each species were in the sun and in the shade. From this I was able to plot the temperature range for each species showing when it felt too hot and when too cold. The values varied with the species. This project seemed to me an excellent way to study one aspect of mammalian physiology outside the laboratory, where the animals had completely free choice and where conditions were less abnormal than in it, but I received few requests for reprints, possibly because the article was published in the little-known International Zoo Yearbook (Dagg, 1970).

This temperature study necessitated extended periods of counting individuals in the deer and antelope paddocks such as that of the blackbuck, which was large and crowded. I made notes at the same time on what individual animals were doing. My interest intrigued the keeper, Peter Newman, so we often discussed antelope behaviour in depth, wondering if it might be possible to write a small book that would appeal to zoo visitors. I wrote up a few chapters of our proposed book and sent them to several publishers, but none was interested. This surprised me at the time, because I found the subject of animal behaviour fascinating. It seemed to me obvious that visitors to the zoo would want to know why the animals they were looking at behaved as they did. Now that I am older and more cynical, it seems less surprising that our project was unacceptable.

While in Sydney I received a letter from the Department of Zoology at the University of Guelph where I had taught the year before asking if I would like to be an assistant professor teaching three term courses (lectures and labs) a year for $12,000. I accepted immediately. It would mean commuting 20 km each day from Waterloo, but being a professor was my ambition. The chair, Keith Ronald, was supportive of my teaching and research, which was heady after the lack of interest my colleagues had shown up to then. I was euphoric.

(l to r) Anne’s daughter Mary, Mary’s friend Anna Edwards and Anne’s son Ian.

About the time my job started, the women's movement was gathering steam but it passed me by almost completely. Each weekday I spent in Guelph, and each late afternoon and evening looking after the children who had a baby-sitter responsible for them after day care and school until I got home. The children were usually in bed by eight, when my husband and I often prepared our lectures for the next day for another hour or so. I was too busy for any additional interests beyond the relaxation of badminton, tennis and Scottish country dancing.

Hugh, Anne, Ian, Ian & baby Mary.

I found teaching stimulating. In the small classes of thirty or fewer in mammalogy and wildlife biology we were able to discuss the course contents in depth. For the large first-year classes I had to become a show person. I felt sorry for the students who had to learn in this way, as a body taking notes with little chance of asking questions. I made a point of learning the students' names by hanging around after class to chat with them. Later, I handed back tests before the lecture started to the dozens whose names I knew which startled and pleased them.

“I had taken a summer course in economics for fun, but I had not appreciated then how much money could drive almost everything in modern society. ”

My first connection with sexual bias, entirely theoretical, arose out of a student project started by Dave Whitelock for the wildlife management course I taught (Dagg and Whitelock, 1969). We surveyed a large number of students to determine who were hunters and who were not. Not surprisingly, most of the hunters were male, which meant in turn that most of the government money earmarked to improve hunting in Ontario benefitted men much more than women. For the first time I thought about the political connection between taxpayers' money and the government agenda. The realization was momentous; I had taken a summer course in economics for fun, but I had not appreciated then how money could drive almost everything in modern society.

Another research project also arose because of my interaction with students. In my course on mammals, I liked to spend some time on species familiar to the students. One day when we were discussing rabbits, a woman volunteered that they really were a pest in the city because they ate vegetables and other plants. Not being a gardener, I had never thought of city rabbits as anything but wonderful. This led me to ruminate on where various urban mammals and birds were found, and why -- about the city as wildlife habitat. I devised a survey, carried out by two students financed by a small grant, in which large numbers of house owners in selected districts of Kitchener and Waterloo were asked what species of wildlife they had seen on their property, how often they were seen, and whether they liked having them there. Their responses were then correlated with such things as expensiveness of housing and nearness to bush and park areas. This was one of the first papers devoted to what would become the burgeoning subdiscipline of urban ecology from a nature rather than a planning point of view (Dagg, 1970).

I carried on with this work in the mid-seventies in a project with local naturalists to study and compare urban and suburban bird populations (Campbell, Schaeffer and Dagg, 1975; Campbell and Dagg, 1975; Campbell and Dagg, 1976). During one day each month several of us walked a prescribed route noting all the birds we saw or heard. I was given the urban core because my knowledge of bird species was less than that of the other participants. Some of our bird studies were financed by small grants from the federal government. The man who oversaw such work once came to my house for breakfast while we discussed various projects. He remarked that payment of minimum wage, which we were receiving, was about right for a housewife such as me. (I wish I'd asked him to pay for his food.)

My last paper connected directly with data I had accumulated from observing giraffe in the wild was written with Aaron Taub, a colleague in veterinary anatomy at the University of Guelph (Dagg and Taub, 1970). We decided to study flehmen, or "urine testing," a behaviour I had watched in the Transvaal. A male giraffe would approach a female, hover about until she urinated, then collect in his mouth some of the urine as it fell to the ground. Then he raised his head somewhat and curled back his upper lip, remaining stationary in that position for many seconds. His object seemed to be to assess the hormone content of the urine to determine if the female was coming into heat and would want to copulate. Our paper included a literature search on the behaviour, which has been reported in many hoofed animals and in members of the cat family, my field observations of the behaviour in giraffe, and Taub's anatomical description of how flehmen might work. We concluded that the nasal Jacobson's organ was not involved in the phenomenon, but this assessment was probably wrong, judging from more recent work.

I wrote a short taxonomic paper on giraffe subspeciation about this time with W.F.H. Ansell (Ansell and Dagg, 1971), and later a note (Dagg, 1977). In my search of the literature I had come across a 1896 description by Rhoads, a hunter from Pennsylvania, of a giraffe he called Giraffa australis. The description closely resembled that of the reticulated giraffe which was named and described in 1899. The name reticulata, first applied to a species and then downgraded to a subspecies, continued to be used by scientists interested in the giraffe, even though the rule of priority stated that the correct name was australis. Ansell and I reviewed the history of the confusion, then recommended that the name australis be officially rejected. No one contested our argument, so our recommendation was accepted. I enjoyed delving into topics such as taxonomy, because it gave me some idea of how the discipline functioned so I could teach about the subject with some authority.

By this time I had been awarded grant money ($7,000 I think) from the government to help set up my research program at the University of Guelph. I used it to buy a Super-8 Camera to take films of animals, for a projector to view the films, and for an editor to study one frame at a time. I spent as little as possible to make the money go a long way. My background was in the locomotion of large mammals, so further locomotion work made sense, but I wanted to diversify. I was tired of sitting alone day after day in a darkened room, looking at images of animals rather than the animals themselves. With computer technology being introduced into this field, the future looked ever more technical. It did not appeal to me. I wanted to do research on how animals sensed their environment, and how they thought about what they sensed.

The flehmen study had interested me in olfaction, so I next carried out a study with the help of a graduate student, Doug Windsor, to determine the sensitivity of smell in gerbils (Dagg and Windsor, 1971). We built a T-cage with progressively smaller concentrations of gerbil urine at one end of the T arm and plain water at the other. Since the gerbils were attracted to the urine smell, they turned in its direction when they reached the end of the maze. Only when the concentration of urine was too low for them to distinguish it would they choose either T arm at random. We found that gerbils, like mice, had a remarkably sensitive sense of smell.

Two undergraduates, Mary Gartshore and Larry Bell, and I carried out other experiments with scent, trying to find out just what the smell of its urine meant to a small rodent. Unfortunately, the students who worked in the evening after classes somehow annoyed one of the animal technicians in the animal rooms. Several times this man destroyed our apparatus, or messed it around so that the results were useless. I complained about this, but was told by Dr Ronald that my students must not upset permanent staff. I finally had to abandon these experiments which might or might not have led to some interesting results, although I did publish a note about the work (Dagg, Bell and Windsor, 1971)

I tried working also with an Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) professor who briefly supplied me with urine from female pigs in heat. I offered this to male pigs to see how they reacted. Before I had any useful results, however, the professor decided, without telling me, that he wouldn't supply any more urine. While working with urine scents I wrote a review article from the literature entitled "Secondary uses of urine" which discussed the various ways urine was involved with behaviour -- to convey scent to other members of the same species (pheromones), for cooling by evaporation, for marking territory etc. As I completed it, I came across a similar article and realized I had been scooped. My paper was never published.